Polycentricity and De-colonizing the Two Publics

July 16, 2019Domesticating the Colonial Leviathan towards Afro-Democracy

By Olusegun R. Babalola

Knowing where we are in our community is all about shared history and the special way we do things – our traditions. These traditions make our past an organic part of our lives, and make the lives we live so much richer. They also, at the same time, give us something precious we can pass on to our children. There is nothing wrong with being “modern” or up-to-date, but the idea that this means we should just cast off all traditions and roots that give us our place in the world is very damaging indeed, and is clearly causing many problems, whether social, economic or environmental, across the globe.

- HRH The Prince of Wales, the Forward in Tradition Today; Continuity in Architecture and Society. Edited by Robert Adam and Matthew Hardy; [I.N.T.B.A.U., WIT Press, Southampton, Boston 2008] p viii

Forty-four years after Olusegun Obasanjo led in the creation of the present Nigerian democratic regime in 1979, he would humbly admit it’s woeful and utter failures, disowned it vehemently and ask us “to stop being foolish and stupid” and seek for Afro-democratic reforms. The problem is that Nigeria, as other African democracies, have not been able to domesticate the colonial Leviathan inherited from their colonial past. Afro-democratic reforms must start with two things. First is the de-colonization of the “two publics” of the amoral and colonial public; and the exclude moral, primordial and indigenous public into one polycentric public within genuinely decentralized local government for an equally genuine self-government as found in the West. Secondly, is the re-constitution of the moral, primordial and indigenous public into institutions to nourish character. Having achieve these two things, we would have created the very basis to create our Afro-Democracy towards what Obasanjo also called the Nigerian Dream, which includes African leadership

Just as Alexis de Tocqueville attempted to give democracy its self-knowledge by revealing its evil and advantages in his Democracy in America, I would also attempt the same here, with focus on Nigeria and Africa towards what Leo Strauss called the “today’s civic self-understanding and renewal.”[i] I would here posit what could be the very basis of an enduring Afro-democratic reforms proposed by the former president, Obasanjo.

And this is especially prepared for the Nigerian youth, that they may know what they are up against. However, writing a long and thorough account, which Tocqueville enjoyed, is unfortunately now a luxury. Nevertheless, I would attempt to keep my own account short and thorough at the same time. The place to begin is the Nigerian Dream.

Nigerian Dream and African Renaissance

“The Nigerian Dream,” was the theme of a speech Obasanjo once gave on March 26, 2011 at the Eagle Square, Abuja, the capital city that he is one the major creators. Though, this speech was made during a political campaign for a presidential candidate and a party, these excerpts are classic, timeless and enduring eruptions from the unconscious mind of quintessential statesman who have bled and served his country, and wants the best for it. These excerpts are the core platform on which to secure our national evolution through genuine political and economic reforms. Obasanjo, here speaks of common Nigerian “aspiration, ideal, hope, objective target,” “identity” and “something to fulfil.” According to the quintessential statesman;

“I see the Nigerian dream of a land of unity in diversity, equal opportunity, land of freedom and choices; land of prosperity, fairness, peace and justice; land of love, care and harmony among its people; … and land where no one is oppressed, discriminated against, enslaved or endangered … This is an attainable dream.”

Obasanjo noted that sacrifices have been made “in the past for unity, stability and democracy in Nigeria in giving their lives, shedding their blood, or going to prison. I personally have done two out of those three sacrifices and I am ready to do the third if it will serve the best interest of the Nigerian dream.” Obasanjo also stated;

“with common identity as Nigerians, there is more that binds us than separates us. I am a Nigerian, born a Yoruba man, and I am proud of both identities as they are for me complimentary. Our duties, responsibilities and obligations to our country as citizens and, indeed, as leaders must go side by side with our rights and demands. There must be certain values and virtues that must go concomitantly with our dream. Thomas Paine said “my country is the world”; for me, my country I hold dear.”

Against the enemies of the Nigerian Dream, Obasanjo states that the

“… resort to sentiments and emotions of religion and regionalism is self-serving, unpatriotic and mischievous … It is also preying on dangerous emotive issues that can ignite uncontrollable passion and destabilize if not destroy our country. This is being oblivious of the sacrifices others have made in the past for unity, stability and democracy in Nigeria in giving their lives, shedding their blood, or going to prison … Let me appeal to those who have embarked on this dangerous road to reflect and desist from taking us on a perishable journey.”

Whenever, Obasanjo speaks of this Nigerian Dream, or related themes to it, he also speaks of African renaissance. In his Nigerian Dream speech, Obasanjo speaks of Nigeria as a “land respected internationally and playing its rightful role within the comity of nations …” Along this line, he had joined Thabo Mbeki (South African president) and Abdoulaye Wade (Senegalese president) to champion the clarion call for an African renaissance in early 2000s. Such call, with other factors, had contributed to the transformation of Organization of African Unity into African Union in July 2002 and advancements made in the 2007 African Charter African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.

This African renaissance also featured in Obasanjo panel’s final report presented by to the AU 21st summit in May 2013. As the chairman of a High-Level Panel on Alternative Sources of Financing for the African Union, Obasanjo spoke of hope and fear. Hope; “that there are wonderful opportunities opening for Africa today and that if we seize these opportunities opening for Africa surely claim the 21st Century as Africa’s century.” His fear, “that the windows of opportunities will not be opened for too long and if we fail to do what is right when it is right, the opportunities would fly away in our eyes. We cannot ignore peace and security as the foundation of our all-round development and expected progress.” And speaking of doing the right thing at the right time. He also stated;

“acting in solidarity, cooperation and self-reliance. When we act together, truly believing in Pan-Africanism and African renaissance, our people will trust us and the world would take us seriously. That means action that will actualize our vision. It means doing the right thing at the right time.”[ii]

To making manifest Nigeria’s role in African renaissance, Obasanjo wrote in his 2014 biography, My Watch (vol. 3), “A former African head of state said to me, “Nigeria is just not at the table. And if Nigeria is neither seen nor heard, what can the rest do? Yes, it must … be realized that our posture outside is a reflection of our domestic position and strength, confidence, cohesion and security at home.”[iii]

The Great 1975-1979 Reconstruction

Interestingly, Obasanjo have led his generation in the partial application of the Obalufonic science in Nigeria in what could be called the 1975-79 Great Re-construction when the military regime of Murtala/Obasanjo (1975-79) dumped the inherited and British parliamentary system for an over-centralized American presidential system. That regime created the 1979 Constitution that would be modified into the 1999 Constitution by Abdulsalami Abubarka’s Regime (1998-9). And between the two regimes Ibrahim Babangida regime would make some interesting contributions as well, which were unfortunately ignored in the 1999 Constitution.

The Murtala/Obasanjo military regime the synced “the civic form of the city, the political form of the city, and the architectural and urban form of the city” in the creation of a capital towards national vocation. However, the regime omitted the “co-existence of ancient way of life or constitutionalism and a more modern constitutionalism” and as such could not secure “the classical cultivation of virtue and human excellence; good government; political stability; and economic progress.” What is Obalufonic?

The thrust of the “the civic form of the city” or simply, the shared purpose, was the creation of a new pollical order against pan-tribalism, the dominance of one ethnic region over others. Historically, our First Republic was destroyed by pan-tribalism, a soft type of the exclusive and irredentist fascism. It also led to the unfortunate military coups, and counter coups, the most unfortunate Civil War, that followed, and as such the regime was prepared to create another democratic dispensation without it

According to Munoz, this Nigerian context, this ethnic competition for power, called pan-tribalism (or simply tribalism) is “traditionalism” or the ideological manipulation of tradition, as opposed to tradition or the “instinctive” or “natural” continuity.[iv] Tribalism, according to A. A. Akiwowo, is when geo-ethnic groups compete for “places in the class status and power systems of the new nations,”[v] through the ideological manipulation of “identity”[vi] or “primordial loyalties,” which may “have a religious, cultural or ethnic character.”[vii] According to R. L. Sklar, the specie of “pan-tribalism” which is as a result of modern urbanization and the expression of the primordial sentiment of the new class is different from “communal partnership” found in townships where indigenous values and authorities thrive.[viii]

Towards this end, Chapter II on Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy; Chapter III on Citizenship; and Chapter VI on Fundamental Rights were combined as a vital shared purpose of a nation made up of the disparate Nigerian civil societies with sharp religious and ethnic differences.

The Chapter II is somewhat comparable to the American Declaration of Independence, and according to Akinola Aguda, “that Chapter II is an attempt to introduce into the constitution some ideals and concepts in the nature, in a manner of speaking, of Natural Law of a bye-gone era … it would appear to me that the judge must not be allow chapter II to remain a white elephant.”[ix] Nigeria only learned from the 1950 Indian Constitution’s “directive principles and duties of citizens”[x] and the Constitution of Eire, which also lays down certain directive principles of state policy. These constitutional provisions are not enforceable or justiciable in the courts.

The 1979 Constitution secured separation of powers and checks and balances between the executive, the judiciary and the legislature, but legislated the 1976 Local Government Reform which would “the first time the local government will be recognized as a tier-of-government in Nigeria.” However, it imposed a uniform system of administration all over the nation,[xi] deprived the local government of any power of maintaining law and order” and unfortunately excluded the indigenous polities, [xii] that is “ancient way of life or constitutionalism,” and Amongst other features, The good colonial inheritance of customary jurisprudence which accommodates natural law is also preserved in the Chapter VII Judicature to establish a national, an absolute and universal principle against cultural relativism and positive laws in customary jurisprudence. Natural law is often contrasted with the positive law (meaning “man-made law”, not “good law”; cf. posit) of a given political community, society, or nation-state, and thus serves as a standard by which to critique said positive law.[xiii]

The major “architectural and urban form of the city” was the creation of a new capital the Federal Capital Territory –Abuja, which turned out to be a modernist replication of the classical American capital, Washington D.C., which was designed and built based on natural law aspirations. Interestingly, Akinola Aguda, a natural law advocate, was also the head of the Commission, created by General Murtala Mohammed, that came up with the idea of Abuja as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). General Murtala Mohammed must have envisioned Abuja as the home of the natural law against pan-tribalism which Obasanjo’s regime would establish in the Chapter II of the constitution, and in some decades after rule as a democratic president. There was an obvious infatuation with natural law to reinforce the order and common sense against tribalism.

Protests Against the 1979 Draft Constitution

Before the ratification of the 1979 Draft Constitution by the Constituent Assembly made up of representatives from the fixed local governments, there was a great debate. Several great minds argued, and some correctly predicted possible outcomes. There was, for example, a socialist minority report by Yusufu Bala Usman and Olusegun Osoba against the Draft proposed by the Constitutional Drafting Committee (CDC).

Also, the socialists like Ola Oni wanted the Chapter II to be justiciable and they deployed the “mixed economy” in the Constitution as means to making Nigeria “satellite economy” of “neo-colonial capitalist economy;” and noted that the “petty-bourgeois” hopes to keep Nigeria together by “maintaining a balance of ethnic interest, creating more and more states to appease the competitive acquisitive struggle of these bourgeois ethnic leaders.” [xiv] Today, prebendalists effecting a colonial version of neo-liberal policies are in power.

In an article titled “Draft Constitution could lead to Bitter Economic Struggles,” Baba Omojola would also make a revealing prediction. Omojola was asked if the CDC hadn’t made “an attempt to reorganize the society for the better.” His reply has come to pass.

“Yes, they did. That is so far as they tried to stabilize the existing state dominated by them for their own interests. In their attempt to consolidate an exploitative system, their CDC draft is meant to do a balancing act – a marvelous piece of impressive but worthless item of political engineering – that’s what it is. It seeks to reconcile antagonistic interests into a national consensus titled in favour of the propertied classes – foreign and Nigeria. But the inevitable failure of the balance will lead to the precipice where constitutions end and political and economic struggles begin.”[xv]

Prebendal Consequence

Unfortunately, one major consequence of the 70s Great Reconstruction is prebendalism. This particular term was coined by Richard Joseph in 1987 when studying particularly the Nigerian Second Republic which operated the 1979 Constitution. Joseph used that term to explain the Nigerian variant of neopatrimonialism or patron-clientelism. Prebendalism is where civil servants and elected officials have a sense of entitlement to government revenues, and use such corrupt funds to benefit supporters, ethnic kins and co-religionists. The term describes the sense of entitlement that many people in Nigeria feel they have to the revenues of the Nigerian state. Elected officials, government workers, and members of the ethnic and religious groups to which they belong feel they have a right to a share of government revenues. Joseph wrote in 1996,

“According to the theory of prebendalism, state offices are regarded as prebends that can be appropriated by officeholders, who use them to generate material benefits for themselves and their constituents and kin groups…”[xvi]

This variant of neo-patrimonial is also well stated by Lord Atkins Adusei in Obasanjo’s 2014 biography, My Watch (vol. 3). According to Adusei, Nigerian

“decline is self-inflicted even if external forces and events have played a role in it. At the heart of the problem is the neo-patrimonial power system that serves only the interest of the few … “enrichment without development.” The elite capture politics with its concomitant by-product of extreme poverty, inequality, conflict, terrorism, armed robbery, kidnapping, violence, cyber fraud and corruption ought to be dismantled.”[xvii]

In short, prebendalism is about bribing sectional pan-tribalists, who care neither about the profitable continuity of traditions/civilizations in modernity nor political stability and economic posterity, to keep Nigeria one. Whilst this has somehow kept Nigeria one till this moment, it has also made political stability and economic progress impossible.

The New Gambit; Prebendal Pan-tribalism

By the Fourth republic, the dynamics had changed again with a new gambit – the exploitation of pan-tribal and religious agitations, based on real or fictious injustice inflicted by the Nigerian state, in the completion for the pan-tribal control of the rotten prebendal pyramid by the elite.

In this manner, insecurity caused by an aggrieved ethnic or/and religious group becomes a tool for the prebendalist struggles for power and wealth. Let us call this new gambit “prebendal pan-tribalism,” which has become intendedly or un-intendedly a format for organized insecurity as a tool of negotiating power and wealth, which occasionally snowball into separatist movements led mostly by tribalists and prebendalists who still want to constitutionally exclude the indigenous polities. Mogaji Gboyega Adejumo the Publicity Secretary of Afenifere noted this prebendal pan-tribalism on March 14;

“No president since 1999 has escaped this scourge, coming with the political sharia against Obasanjo, the Niger Delta violent political agitation of Obasanjo and Yar’Adua …Boko Haram religion-later-turned-political instrument to embarrass a sitting southern Christian … Jonathan, who was told to convert to Islam, followed by the kidnapping extraordinaire of the Chibok girls type …”

To these we could add the political agitation of IPOB during Buhari’s regime; the ongoing pastoral Fulbe menace during President Tinubu; amongst others. Thus, we are back to square one. Pan-tribalism has returned through the back door. Lord Adusei also noted the absence of rule of law;

“Nigeria’s ostrich approach” to regional problems; how the declining regional power of Nigeria coincides with rising regional power of France in West Africa and the rising regional and global of South Africa; incapacity of the Nigerian state to establish rule of law with the Nigerian pirates in West African coast, the “Boko Haram and Ansaru” terror, armed robbery, kidnapping, hostage taking, oil smugglers, “communal, ethnic and tribal conflict and tension.” He noted the Nigerian inability to solve domestic problems and provide global and regional leadership and how a “power vacuum has been created which is increasingly being filled by criminal gangs and hegemonic external powers, notably France, the United States and Britain.”[xviii]

Matters Arising; Case for Afro-Democratic Reforms

Widely reported in the media, on November 20, 2023, “Former President Olusegun Obasanjo says African countries must discard the liberal democracy introduced to the continent by the Western countries” and should practice “Afro-democracy”.[xix] Obasanjo stated the majority of people are kept out of the government under liberal democracy, that

“These few people are representatives of only some of the people and not full representatives of all the people. The weakness and failure of liberal democracy as it is practised stem from its history, content, context and its practice. Once you move from all the people to representatives of the people, you start to encounter troubles and problems. For those who define it as the rule of the majority, should the minority be ignored, neglected and excluded? In short, we have a system of government in which we have no hands to define and design and we continue with it, even when we know that it is not working for us.”

He stated that “Those who brought it to us are now questioning the rightness of their invention, its deliverability and its relevance today without reform.” Obasanjo added “that the continent must look inward and outward to understand how another form of government can be adopted.” Obasanjo demands for a reform:

“We are … to stop being foolish and stupid. Can we look inward and outward to see what in our country, culture, tradition, practice and living over the years that we can learn from? Something that we can adopt and adapt for a changed system of government that will service our purpose better and deliver. We have to think out of the box and after, act with our new thinking … examine clinically the practice of liberal democracy, identify its shortcomings for our society and bring forth ideas and recommendations that can serve our purpose better.”

TheCable noted that this “is not the first time the former president would talk about liberal democracy not working in Africa” and that in “an exclusive interview with in September, Obasanjo said “The liberal democracy we are copying from settled societies in the West won’t work for us”. Obasanjo’s vision of the Nigerian Dream dedicated to African renaissance is now more recent upgraded to include Afro-democratic reforms.

It is in understanding with empathy why this Obalufonic science was not properly applied in Nigeria that we would understand how this science can be properly applied towards political stability and economic progress. So, what was it that was done wrong in the 1979 and hence 1999 Constitution? With all these massive investments in natural law or what Leo Strauss called classic natural right, how come the experiment have not all together been successful? How do we empower a government to do what should have been done?

On the last question of empowering a government to do carry out the necessary reforms, I have no answer. However, I can answer what the Murtala/Obasanjo military regime should have done.

Nico Steytler’s Revelation

Nico Steytler in his 2016 Domesticating the Leviathan: Constitutionalism and Federalism in Africa,[xx] sheds eminent lights on how we could negotiate the Afro-democratic reforms, what Louis J. Munoz defined as “constitutional autochthony” in opposition to the “American Paradigm of Modernization.”[xxi] Steytler noted that the third “wave of constitution-making” in Africa since the end of the Cold War which seeks “to divide power horizontally and vertically has not produced constitutionalism and, where attempted, federalism or devolution.”[xxii] Steytler sheds lights on the four continuities (and discontinuities) of the colonial Leviathan in the present African post-independent Leviathan, which has compromised African liberal democracies into “quasi-democracies” or “illebral-democracies” [xxiii]“ where the “centralisation of the African state did not, as promised, lead to development, but to its opposite – conflict and skewed underdevelopment.” [xxiv]“

First is that what we have is an un-accountable, despotic, over-centralized, colonial and Hobbes’ Leviathan. Steytler argued, “that Thomas Hobbes’ The Leviathan captures the challenge that post-1989 constitution-makers faced in confronting the highly centralised state in Africa.”[xxv] This is inherited from the colonial state which “embodied the Leviathan, which the post-independence state simply replicated.”[xxvi] According to Steytler, “In the West, Hobbes’ Leviathan had become the foundation of the modern central state. The colonial structures of the European powers transplanted the responsibility of providing peace and security to the empire, thereby by extension to the colonial state.[xxvii]”

Hobbes concerns were “restoration of order” and “commonwealth” dedicated to “peace and security” against the Hobbesian condition, “the war of all against all.”[xxviii] This is to be anchored by the sole ruler, “the Leviathan” with “sovereign power” and without divided powers.[xxix] Nevertheless, “the absolute rule of the commonwealth” is not identical to “arbitrary rule or partisanship,”[xxx] but “demands equity from the sovereign” which unfortunately is “not up for discussion with the sovereign,”[xxxi] The Leviathan regardless of the established “social contract” is “therefore not accountable to the people though it demands “deference and obedience.”[xxxii] However, “Hobbes admitted that injustices would be met by the ‘the violence of enemies’ and with “‘rebellion, and rebellion with slaughter.””[xxxiii]

Steytler affirms that the “analytical framework of Hobbes’ Leviathan provides a sharp optic by which to make sense of both the evolution of constitutional orders since colonialism and the fate of constitutionalism” in Africa.[xxxiv] The “post-independence state came to rest on foundational principles as monolithic as its predecessor the colonial state in justifying its own existence … Despite the rhetoric of nation-building and economic development, the incumbent Leviathans had more immediate short-term goals in mind; control of political power enabled access to wealth and privilege for the privileged view or ethnic group.[xxxv] As such, the “Postcolonial constitutions perforce had little legitimacy; they were mostly imposed, and the framework was foreign not only to the lived experience of colonial rule but also to indigenous forms and values of governance.”[xxxvi]

The second is the what Peter Ekeh had earlier defined as the “two publics” of the amoral and colonial “civic” public, on one hand, and the moral, indigenous and “primordial” public, on the other. [xxxvii] Because “Undivided political authority was seen as the only way to govern the post-independence state,” effective “decentralisation was held as a threat to nation-building and the ideology of development, with the result that no meaningful power was delegated to local authorities.[xxxviii]” Steytler also noted;

“On the one side is the formal state (acting in its own interest or for an exclusive group) and on the other are informal governance institutions (social institutions and processes working for people’s daily survival). In summary, the constitutions do not stand central to the ordering and regulating of power relations in the society.”[xxxix]

Just as the colonial powers had “brought traditional authorities into its service,”[xl] the new African leaders continued the same structure. This is what Munoz calls “fatal dualism.”[xli] According to Sheldon Gellar; “Under colonialism, indigenous African societies lacked the freedom to establish a new political order. Laws enacted during the last phases of colonial rule extended full political and civil rights to large segments of the African population in many countries. At independence, the leaders adopted liberal western constitutions based on European models with little consultation of the people.”[xlii] Steytler noted; “In addition to the opposing regional power bases that could potentially check the powers of the centre, traditional authorities were also seen as barriers to the development aspirations of the post-independence African state.”[xliii]

Worse, the program of “de-ethnicisation” is devised by African leaders for the sake of nation building. In Steytler’s words; “Traditional authorities were perceived as competing centres of loyalty, and the new rulers sought, in the patriarchal language of Hippolyt S. A. Pul, ‘to emasculate’ and ‘effeminate’ them in the name of de-ethnicising post-independence countries.”[xliv] It is this policy of de-ethnicisation that Wole Soyinka called “the policy of glamourised fossilism” in his 1965 Kongi’s Harvest.

The third is the demand for obedience by the Leviathan even without accountability and equity or natural right. But instead of “obedience” what we have is what Tocqueville called “general apathy” and absence of citizenship, all manifesting as pan-tribalism stated above. General apathy, propped up by individualism is possible because in the first place due to the break with the traditions, rise of equality of condition and the lack of social ownership of the state. “There is thus a ‘pervading disconnection between the rulers and the ruled in the postcolonial state in which the majority of Africa’s citizens live outside the postcolonial state’.”[xlv]The amoral state is seen for what it is as an imposition without accountability to the people.

As Peter Ekeh taught, there exists “two publics instead of one public, as in the West;” the moral “primordial public” and the colonial and amoral “civic public.” And the “dialectical relationships” between them is the genesis of “Many of Africa’s political problems.” [xlvi] Whilst both are kept separate the former is imposed on the latter. As a result, the amoral public becomes the spring board of pan-tribalism, defined above. Pan-tribalists are never interested in the genuine continuity of traditions/civilizations evident within moral primordial public, unlike the communal politics “which constitute a value per se,” for pan-tribalists, “it has primarily an instrumental value; it is a weapon to be used in the contest for political supremacy in the national arena.”[xlvii] Gellar also notes that “Many societies in precolonial Africa were self-governing communities that fiercely defended their independence. The imposition of colonial rule was often accompanied by the demise of local liberties. During decolonization and after independence, African political elites placed more emphasis on gaining control of national level institutions rather than seeking to reestablish local liberties and decentralized democratic governance.”[xlviii]

The fourth is the absence of peace, security and hence, political stability for economic development which reveals an irony that the centralized state is actually weak, because it cannot provide peace and security. “The centralisation of the African state” according to Steytler “did not, as promised, lead to development, but to its opposite – conflict and skewed underdevelopment.” [xlix]“

The paradox is that the “de-ethnicising post-independence countries” became “one party states” which “turned into ‘monoethnic hegemonies’[l] since the “control of political power enabled access to wealth and privilege for the privileged view or ethnic group.”[li] In that way “monoethnic hegemonies”[lii] became the general motivation for pan-tribal competition for power.

The pan-tribal competition for power is further worsened by cultural relativism.[liii] As Yash Ghai argued, “that society is divided on the values of the constitution – divisions that are often articulated on the grounds of cultural relativism.”[liv] This pan-tribal struggle for monoethnic hegemonies is made possible by the existence of the “two publics.” Unlike the colonial era, there has been violently more cases of anarchy and despotism in our history, caused by the amoral struggles for wealth and power by the pan-tribalists. Examples are the collapse of the First Republic, our litany of military coups, and the Civil War. So, when the chicken came home to roost, there was no moral agency to confront it. All are received with Apathy. Still.

Unfortunately, it is getting more vicious and worse. The pan-tribal competition for power led to the new gambits of prebendal despotism in the Second Republic and to prebendal pan-tribalistic anarchy in the Fourth Republic. It is a vicious circle, within which we are trapped, by ourselves. In short, the constitutional and formal exclusion of the more accountable “traditional and informal governance structures” leads to insecurity, and hence, the failing state. And as result, as Ghai suggested “in the West it was society that shaped the state, while in colonial and post-colonial Africa, the state has so far shaped society.”[lv] This is one powerful handle of coloniality which must be reversed, discussed below.

Thus, “Hobbes’ The Leviathan” still “captures the challenge that post-1989 constitution-makers faced in confronting the highly centralised state in Africa,” which failed to “fundamentally change the exercise of sovereignty” and “domesticate the Leviathan.”[lvi] Therefore, the “liberal constitutions did not change the nature of the state in many countries and federal systems have not emerged.”[lvii]

Nico Steytler’s Diagnosis

In final analysis, Steytler points to the “larger problem – that of the nature of the social compact as articulated in the constitution,”[lviii] which reveals “the constitutions are yet to be a social compact of competing social forces that have the interest and capacity to ensure compliance,”[lix] and also, the “problems with constitutional design itself.”[lx] “Constitutionalism, the practice of constitutional democracy” according to him “is the product of three key factors, politics (state), the economy and society,”[lxi] or “through the struggle between the government, local elites, and business circles.’[lxii] There is the two-way relationship between – the three factors (politics, the economy and society), on one hand and on the other hand, the constitutional order which is a result of changes in the three factors, and their interaction with one another.

This focuses on “societal changes” – on “how change could be effected” on the “establishment of constitutionalism” through “values and processes” that are directed at how the transformed society could domesticate the Leviathan, and as such through “a slow and incremental process.”[lxiii] Steytler concluded;

“constitutions are not the grand bargain of selfgoverning associations of a polycentric society, covenanting among themselves how to domesticate the Leviathan, the citizens or interest groups are unlikely to come forward ‘to pay the price of civil disobedience’ in challenging the constitutionality of governmental action[lxiv] and finding a receptive and independent judiciary.[lxv] [italics is mine]

Steytler would attribute “the failure of constitutional orders” to the absence of “social compact of competing social forces that have the interest and capacity to ensure compliance.”[lxvi] Only one problem remains, as Steytler observed and that is the “absence of political will.”[lxvii] The “prevailing forces are dominated by the ruling elite/state monolith, which has little interest in limited government”[lxviii] or with “no real interest to curb its own powers.”[lxix]

Vincent Ostrom’s Twin Advice

Steytler also quotes Vincent Ostrom’s twin advise for Africans on how to domesticate the Leviathan. The first is “that Africans could learn how their former colonial masters” domesticated “the Leviathan in old and modern European history first by securing the recognition of the autonomy of the organs of civil society,” and “by dispersing power at the centre through the separation of powers.”[lxx]

Along this line, Steytler also noted that in Europe “popular sovereignty” replaced “the ruler as the sovereign, the linguistic, ethnic and historical coherence of the people first became a principle, and later through state-building a reality as well.”[lxxi] The same happened in the United States where “the spectre of Leviathanian tyranny” was address by “the liberal democratic philosophy of John Locke and others in Europe and the federal ideals of Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in the Federalist Papers.”[lxxii] These are very relevant since “the same task was at hand at the end of the twentieth century in Africa.”[lxxiii]

Secondly, Ostrom challenged Africans “to discover in their own history, values, experience and traditions, a path that leads away from the highly centralized state and towards self-governance.’”[lxxiv]99

It is in following Ostrom’s advises that one encounters decoloniality.

Decoloniality

The most important question here is why and how a decolonial project could ever learn from the West, which itself is the capital of coloniality? As Soyinka noted “The fundamental problem for the African intellectual who struggles for a cultural renewal continues to be that of reconciling tradition and progress.”[lxxv] However, Munoz and Kolawole Ogundowole, two of my best teachers, gave interesting advices too.

Louis J. Munoz asks why “should we be here in Nigeria still interested in the classics?” In his illuminating book The Past in the Present; Towards a Rehabilitation of Tradition, concerned with the mutual relationship between continuity and change. Munoz quotes Professor Abiola Irele’s 1982 Inaugural Lectures[lxxvi]; In Praise of Alineation which “was intended to focus attention on the historic turning point represented by the African encounter with Europe and its cultural implication” at the “when the Western paradigm is being re-assessed, its undoubted triumphs placed alongside it’s no less obvious inadequacies.”[lxxvii] Irele affirmed, “Indeed, we have been so involved in this civilization that to consider it as something set apart from us is to set it up as an abstraction.”[lxxviii] Engaging with the Western civilization would “enable us to participate in an informed way in the debate on the future of a civilization whose continuing relevance to our lives is likely to endure far into the future.”[lxxix]

Also, whilst presenting the case for de-colonization in his famous 1988 book Self-Reliancism; Philosophy of a New Order, Kolawole Ogundowole noted that both Frank Fanon and Julius Nyerere “recognized that the process of integration between the new state and Eurocultural-based societies (Europe and North America) is far from complete.” [lxxx] However, whilst Nyerere “calls for a return to pure indigenous situation” Fanon “seemed to think that while the process of integration is far from complete, it has gone too far to be reversed, above all, at philosophical level.”[lxxxi] For Fanon “the development type inspired by Europhilosophical heritage is as unethical as it is economically and politically infeasible for any state to imitate it. Fanon conceives the world of the new state and Eurocultural reality as poles apart both in practice and in thought.” [lxxxii] It is in this context “that Fanon implored students in the new states to adopt creative approach to the study of Europhilosophical and Eurocultural heritage such that can ensure total de-colonialization, rather than merely quoting Montesquieu.[lxxxiii] Ogundowole states;

“With Fanon a definite new orientation in philosophy seems to be in the making. His views on many issues tend to indicate, whether freely or not, peoples in the new state are irrevocably involved with fundamentally Eurocultural world, and that in order to make their own contributions to their own and the rest of the world’s future, they must above all comprehend the powerful cultural forces which threaten to overwhelm their indigenous concepts and values. … So while the economic and political facts make it impossible for philosophers in the new state to hold onto Europhilosophical tradition and illusion of universality enjoyed by it, they also seem to make it impossible for them to sustain an alternative illusion of autarchy, either. For what mankind, and so peoples of the new states, require today is an alternative of genuine truly universal nature, since not only peoples in the new state are in urgent need of a new orientation but even peoples of the Eurocultural world as well. In this context the conscious particularity of Nyerere’ Ujamaa, Kaunda’s Humanism and Senghor’s African Socialism, is if anything, even less true to the facts of the new state predicament that are the oppressive Europhilosophical tradition and the social and international economic practices based on it. [lxxxiv]

As such, what follows is based on Ostroms twin advises, carefully informed by Munoz’z and Ogundowole’s advises as well.

Two Afro-Democratic Reforms; Things the 1975-1979 Military Regime should have Done

All the observations by Steytler made above, are still evident in our 1999 Constitution. Distracted by the modernization paradigm and modernism, the military regime omitted the civilizational aspects with respect to cultivation of character, excluded the moral primordial public, and opted for a more “unitary” system against both “pan-tribalists” who exploit tradition and “communal partnership” to whom tradition is a value per se.

Relying significantly on Tocqueville and other scholars, whose names would be mentioned as we progress, on how the West domesticated the Leviathan, I could proffer two major things that the 1975-9 military regime should have done, which would have given us a totally different outcome of constitutional structure and federalism, and that would have resembled what could be called an Afro-Democracy.

The first is the de-colonization of the two publics into a single public, all accommodated within well decentralized, polycentric and self-governing communities or local governments, as the American Founders did. The regime should have built a polycentric order with multiple centers of decision making, overarching rules and spontaneous creation of decision-making centers. And the second is by institutionalizing the moral primordial public in such a way that they can nourish character, directed towards the cultivation of virtue, good governance, “commercial vigor” and the profitable continuity of their civilizations/traditions also as the American Founders did, at least till the eruption of historicism.

First Afro-Democratic Reforms; Polycentricity and De-colonizing the Two Publics

Inspired by the American constitution, constitutionalism and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, “Vincent Ostrom and his associates” too, confronted the advocates of “monocentric” or centralized system, also known as the gargantuan, during the 1960s debate on “public administration reform in American metropolitan areas.” [lxxxv] Vincent Ostrom, C. M. Tiebout, and R. Warren, in 1961, defined the term polycentric;

““Polycentric” connotes many centers of decision-making which are formally independent of each other. Whether they actually function independently, or instead constitute an interdependent system of relations, is an empirical question in particular cases. To the extent that they take each other into account in competitive relationships, enter into various contractual and cooperative undertakings or have recourse to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts, the various political jurisdictions in a metropolitan area may function in a coherent manner with consistent and predictable patterns of interacting behavior. To the extent that this is so, they may be said to function as a “system.”[lxxxvi]

The “concept of polycentricity,” according to Paul D. Aligica and Vlad Tarko[lxxxvii] in their article Polycentricity: From Polanyi to Ostrom, and Beyond, is “a structural feature of social systems of many decision centers having limited and autonomous prerogatives and operating under an overarching set of rules.”[lxxxviii] There are 3 basic element of polycentricity (emphasized by the Bloomington school approach). And these are

(1) The existence of many centers for decision making,

(2) the existence of a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced), and

(3) the existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life.”[lxxxix]

This is a very brief introduction into what Steytler calls “a polycentric society” which explains what he meant by constitutions “the grand bargain of self-governing associations of a polycentric society, covenanting among themselves how to domesticate the Leviathan.”[xc] [italics is mine] Constitutionalism,

“the practice of constitutional democracy,” according to Steytler, is the product of three key factors, politics (state), the economy and society.”[xci] There are two polycentric reforms towards the rectification of polycentric politics (state), the economy and society that could lead to the desire constitutionalism. The two polycentric and Afro-democratic reforms are

(1) decentralization and constitutionalising the local self-government with all the three elements of polycentricism; existence of many centers for decision making, existence of a single system of rules, and the existence of a spontaneous social order; [xcii] and

(2) the decolonization and the destruction of the two publics of “the formal state (acting in its own interest or for an exclusive group)” and the “informal governance institutions (social institutions and processes working for people’s daily survival)” [285] into one single moral and polycentric public.

Both would create a political “island of polycentric order” which over the time “presses for polycentricism” in the society and the society, and after those, in constitutional reforms, constitutionalism and federalism. The place to begin is why “the grand bargain of self-governing associations of a polycentric society, covenanting among themselves how to domesticate the Leviathan” is absent?

From Tocqueville we learn that the enemy of liberal democratic constitutionalism is neither “anarchy” nor “despotism,” but general apathy (supported by individualism) which is the actual mother of both anarchy and despotism. The history of such state inflicted with apathy is thus a cyclic history of anarchy and despotism. Yet, “general apathy” and “individualism” are as a result of both the destruction of the erstwhile pre-modern intellectual and moral orders anchored by the non-separation between religion and political order; and the “irresistible” as well as the potentially profitable rise of the modern notion of equality of condition. These were well captured by Tocqueville in the French troubled history after the French Revolution[xciii] and of Mexico in the 19th Century.[xciv] Along this line, Steytler quotes the famous Tocqueville’s critique of electoral democracy, that does not necessarily empower citizens. ‘A constitution republican in its head and ultramonarchical in all its other parts has always struck me as an emphemeral monstrosity.’[xcv] Furthermore, Tocqueville himself noted;

“When a nation has arrived at this state it must either change its customs and its laws or perish: the source of public virtue is dry, and, though it may contain subjects, the race of citizens is extinct. Such communities are a natural prey to foreign conquests, and if they do not disappear from the scene of life, it is because they are surrounded by other nations similar or inferior to themselves: it is because the instinctive feeling of their country’s claims still exists in their hearts; and because an involuntary pride in the name it bears, or a vague reminiscence of its bygone fame, suffices to give them the impulse of self-preservation.”[xcvi]

Despotism saps the emergence of a polycentric order with over-centralization whilst subjugating the actual “island of polycentric order” [xcvii] of indigenous institutions capable of pressing for polycentricism. [xcviii] This is a major component of the coloniality of power. The consequences of this coloniality have further led to the de-ethnicisation of indigenous institutions to foster coloniality of knowledge, through knowledge production by the amoral public. And other pathologies which are species of apathy, spurning anarchy, such as “monoethnic hegemonies,” cultural relativism and ethnic competition for power which manifesting as pan-tribalism, prebendalism and prebendal pan-tribalism, have become some unnatural and altered state of existence, furthering the coloniality of being. As such the “emergence of societal forces” vis-à-vis the “interaction and bargaining processes between government and society” become elusive.

The irony is that the centralized state is weak, because it cannot provide peace and security. Whilst both anarchy and despotism frustrate political stability and economic development, apathy further saps “initiative and optimism” needed for the surest cultivation of self-interest rightly understood in a liberal democracy, which Tocqueville established based on “economic sense.” Within this organized chaos, pan-tribalist elites, with access to labour and natural resources, and most importantly to brute force, exchange batons to rule on behalf of some recalcitrantly colonial economy, which in our age is called neo-liberalism. As a result, the strategic nurturing of self-reliant and private industrial corporations, who could add value to raw materials, in local governments necessary for industrialization becomes impossible. Instead, we have local authorities and federating units go cap-in-hand for federal allocations, rather than becoming productive economic centers. Cumulatively, we export raw materials and import finished products

Coloniality of power and knowledge transmogrify colonial subjects to “victims of the coloniality of being” banished in “a condition of inferiorisation, peripheralization, and dehumanization,”[xcix] all robbed of their humanity and citizenship. What we have are “illiberal democracies or semi-democracies,”[c] without citizens. From what has been said, as well as what are omitted so as not to bore the reader, it is obvious that the end of colonial administrations in Africa is not the end of coloniality. According to Falola,

“When one subjects the end product of colonization and coloniality to a thorough examination, one quickly sees that it has been effectively deployed to drive three significant things in the lives of the marginalized community who are at the bottom end. These are realized as the coloniality of being, coloniality of power, and coloniality of knowledge.” [ci]

Generally speaking coloniality of knowledge production secures the coloniality of power established for economic coloniality, and through that colonial subjects are turned into less than human zombies (apologies to Fela Anikulapo Kuti), without initiatives and optimism, without character, as despicable victims of the coloniality of being.

The strategic unification and decolonization of the “two public” into a single moral and polycentric public would lead on one hand to the creation of a strong society, as argued by Steytler; and on the other hand, it would enhance commercial vigor, as also argued by Carol M. Rose.[cii] And both the strong society and the commercial vigor, together with the polycentric politics, secured by the decentralization and constitutionalising the local self-government with all the three elements of polycentricism would create a legitimate constitutional order, constitutionalism and federalism with a high dose of compliance, and hence, rule of law.

For Tocqueville, the science of association, which includes local government as the fundamental basis of liberty, is the mother of science in a democracy.[ciii] Tocqueville thought that only by association can people stand against the government[civ] and that voluntary associations are to “supply the individual exertions of the nobles, and the community would be alike protected from anarchy and from oppression.”[cv] The “principle of self-interest rightly understood – “the heart of Tocqueville’s resolution of the problem of democracy,” [cvi] is but a product of the local self-government; “the locus of the transformation of self-interest into patriotism” … “transform essentially selfish individuals into citizens whose first consideration is the public good.”[cvii] Steytler clearly noted this too that the local government is the “participatory institutions of self-government.”[cviii]

And along these lines, the extensive employment of the three attributes and indicators of polycentricity; the IAD framework for each particular the traditional and informal governance structure; as well as Sheldon Gellar idea of Tocquevillian Analytics which he explore in his 2005 Democracy in Senegal: Tocquevillian Analytics in Africa, Interestingly, in Tocquevillian Analytics: a Tool for Understanding Democracy in Africa and the Non-western World, would all be “useful” (to use a Touqueville’s term). Yet, not only could “Tocquevillian analytics” be useful is our quest for Afro-democracy, they are fundamental decolonial tools against the recalcitrant Euro-American coloniality. According to Gellar, “Tocquevillian analytics” provides a more profitable analysis to “Africa and other parts of the non-western world,”[cix] just as it was for 19th Century France which had “similar kinds of problems in sustaining democracy”[cx] and “lacked traditions of political freedom,” [cxi] and was troubled by the transformation from an aristocratic society to a democratic one. [cxii] As Vincent Ostrom noted “Tocqueville’s Democracy in America was not preoccupied with an exotic experiment in the North American continent. Rather he was concerned with the viability of democratic societies under circumstances of increasing conditions of equality among mankind.” [cxiii]

So far, we have been speaking of polycentricity in relation to the United States and liberal democracy, at large. However, it would be useful to say a few things about polycentricity also in China as a contrast to what we have in Nigeria. David S.G. Goodman and Gerald Segal, in a 1994 article’ China After Deng: The Prospects for Polycentrism and Democratization, wrote that “China is already characterized by a high degree of regionalism that has dramatically altered the workings of its political system and is coming to influence domestic style. National unity may not be in question but China increasingly polycentrist.”[cxiv] They noticed how within China “the impact of de-centralization, regionalism, national economic integration all seem to indicate the greater diffusion of political power,”[cxv] As a result, even China, and not only United States is more polycentric than us. More than anything both Goodman and Segal noted a Chinese modernization that has not abandoned its past.

“If anything through international economic integration—specific to each economic region – China’s provinces are becoming more rather than less autonomous, least in relation to central government. On the surface an effective federalism seems a distinct possibility in practice, though not in name or law not least because of the absence of a tradition of a rule of law. Chinese culture has long been polycentric; it was only the rigid conformity of the late Qing Empire and the state under Mao sought to portray its centralist aspects.” [cxvi]

It is obvious that the Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren combined critique of the gargantuan, which is coeval to Steytler’s critique of the Leviathan, explains in large part the present predicaments of the African “quasi-democracies” or “illebral-democracies.”[cxvii] But with the two significant Afro-democratic reforms within the Nigerian 1979 and 1999 Constitutions, we would have had a different and profitable basis for constitutionalism and federalism.

Janu Effects and Nourishing Character with Institutions

Polycentric governance, the social philosophy and the “solid empirical research agenda” [cxviii] such as institutional analysis and development (IAD framework) and the social–ecological system (SES) framework by the Ostroms’ Bloomington school from it, according to Andreas Thiel “describes a specific, static structural configuration of governance … This definition aims to provide clues about whether a specific configuration of governance was polycentric. It is not interested in the dynamics of how it emerged, sustains or outlives itself.” [cxix] As a result,

“polycentric governance focusses on static structures of governance without giving much emphasis to the way they are enacted. The latter, however, may be decisive for performance of governance.” [cxx]

For example polycentricity shows how the existence of many centers for decision making. However, it does not tell us how they emerged and how they are sustained. For example, polycentricism cannot tell us how to end the problem of cultural relativism and ethnic competition for power which prop up the problem of mono-ethnic hegemony and is in turn propped up by universal suffrage. How was this confronted in the West?

In the West, and in America in particular, whilst polycentricity is sustained by the ancient or Socratic political philosophy and the Aristotelian political science which survived as what Carol M Rose called the “ancient constitutionalism” [cxxi] in local authorities, it’s emerged through the new political science which Tocqueville codified whilst studying democracy in America. In this way, the modern social philosophy of polycentricity is sustained by classical political philosophy. Tocqueville had already hinted us about the importance of Socratic political philosophy. He would propose enlightened doctrine of self-interest rightly understood with otherworldly supports such as religions, even “false and very absurd” [cxxii] and Socratic “the doctrines of a supersensual philosophy” based on the affirmation that “the soul has nothing in common with the body, and survives it” [cxxiii] These must be understood and localized.

Most African democracies are only democracies in paper and not in practice and that is why Nico Steytler called them “quasi-democracies” or “illebral-democracies,”[cxxiv] that ironically cannot secure political stability and development, are ruled over by un-domesticated Leviathan. Yet, one of the major political expedients that can be used to domesticate these Leviathans are local authorities (Alexis de Tocqueville) or cities (Leo Strauss) as the schools of enlightened self-interest (Tocqueville)and moral virtues (Strauss). Local authorities can nourish character through the shared purpose (civic form), the constitution (political form), and the modified physical environment (the architectural and urban form) as found in the American 1787 Northwest Ordinance.

The “dynamics of how” polycentricity “emerged, sustains or outlives itself” is well evident in the works of Tocqueville and Leo Strauss, what Thomas L. Pangle called the Tocquivellean-Straussian political science diagnosis, which is a form or echo of “neo-Aristotelian political science.”[cxxv] This “Straussian-Tocquevillian concern” is “to shore up or repair the pillars of democratic health.”[cxxvi] And this is concerned with “fanning the embers, within modern liberal democracy, of the older republican citizenship and statecraft.”[cxxvii] It is in understanding the dialectics between the “modern liberal democracy” and the “older republican citizenship and statecraft” that one encounters the Janus Effects.

It was this Janus Effects that was codified by Tocqueville as the new science that emphasized enlightened self-interests, local self- government, and other major political expedients including the Arts. And this was helpful in the development of polycentricity by Vincent and Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School.

And only in this shoring the modern constitutionalism with the ancient constitutionalism could we be reminded, according to Strauss, that liberal democracy ‘‘is meant to be an aristocracy which has broadened into a universal aristocracy’’; that ‘‘liberal education is the ladder by which we try to ascend from mass democracy to democracy as originally meant.’’”[cxxviii] And through that we can shore up democracy.

The concern for the small self-governing community as the school of and for republican virtue was one of the major themes pushed by the Anti-Federalists against the Federalists during the founding of the United States. Rose recollected that Anti-Federalists held “that character must be nourished by institutions” and that “initiative and optimism are character traits that the Federalist Constitution needs too, not only for political life but for commerce as well.” [cxxix]

Aside from the Bill of Right, another interesting compromise between the anti-Federalists and the Federalists to me, which is de-emphasized in history, appear to be the Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinances of 1787. Whilst the new 1789 Constitution, based on the de-ontological and modern constitutionalism, was introduced to secure the second polycentric element – “existence of a single system of rules” that the earlier Article of Confederation lacked, the local government principles based on the ontological, civilizational and ancient constitutionalism were preserved and secured within a federal structure through the Northwest Ordinances of 1787, leading to – Janus Effects -a binary complementarity, by means of which the ancient constitutionalism could shore up the lifeless modern constitutionalism with virtue and character. The Federalist 1789 Constitution is like a hardware whilst the 1787 Northwest Ordinance is like the software.

And this shoring up manifests on three levels; civic form; political form; and architectural and urban form, in a two-step transformation. Succinctly, the progression is a two-step transformation from the city of classic natural right and moral virtues, that is, the best politiea (“form of the city” (Pangle 86-7) [cxxx] or regime[cxxxi]or simply “a way of life” [cxxxii]) to the amendable laws of that politiea and from that to the equally amendable physical city created to serve the politiea (classical architecture and urban forms[cxxxiii]). This two-step transformation would eventually lead to an assemblage of the civic form of the city, political form of the city and the urban form of the city, towards what Strauss called “the chief purpose of the city” which is “the noble life” and “the virtue of its members and hence liberal education.”[cxxxiv] And these provide the basis to nourish character.

On this same, Westfall noted; the “purpose a people have in living together defines the civic form they will find useful, and the civil form defines what is required of the architectural and urban form.”[cxxxv] Thus, three things, according to Westfall, make up the polity, and they are

“a shared purpose, a government they construe in order to exercise power justly while reaching for that purpose, and a physical setting which serves their purposes and facilitates their governing themselves.”[cxxxvi] “The primal purpose of any polity (no matter its scale) will be to serve the purposes of its citizens while providing justice in their administration of authority, order in the arrangement of their affairs and beauty in the form of the parts and whole of the physical architectural and urban entity housing it.”[cxxxvii]

Aside from shoring up the modern constitutionalism with character and virtue, the Janus Effect is vital to the creation of a multi-party system, as well as a mechanism of “unsolved and even insoluble problems” to keeps the nation going as long as the generic Manichean duality of two heads or what I call, the Janus Effects, is preserved. And through that “the regime in troubled motion” would find means to negotiate survival during “periods of great tension or struggle over the meaning of the regime”[cxxxviii] as long as the ancient constitutionalism is preserved.

On Socratic political philosophy and the Aristotelian political science, I have here stood on shoulders of Leo Strauss and Thomas Pangle. And on classical architectural theory, I have profited from the thoughts of Carroll William Westfall, a student of Strauss, codified in his co-authored book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Historicism.

Thomas Pangle noted that an encounter with Straussian-Tocquevillian science could make us discover the “important thing” is “above all our way back to the truly most urgent and serious issues that have been buried from our sight.[cxxxix] One of these things buried from our sight is the Janus Effects effected by the Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance. Furthermore, Pangle also stated “‘‘We cannot exert our understanding without from time to time understanding something of importance; and this act of understanding may be accompanied by the awareness of our understanding,’’ by noesis noeseos—‘‘so noble an experience that Aristotle could ascribe it to his God.’’“[cxl]

Whilst Strauss was concerned about the neo-Aristotelean political science that is also Tocquevillean-Straussian political science,[cxli] Westfall, a student of Strauss, is concerned about the classical architectural principles (Vitruvius and Alberti) that is affected by the Tocquivellean-Straussian political science as an echo of “neo-Aristotelian political science.” It was Westfall, a friend, who directed my attention to the Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance. Thus, both Strauss’ resuscitation of Aristotelean political science and Westfall’s resuscitation of classical architectural principles are not only coeval with Tocquevillian political science, but are also tied together by it.

The Northwest Ordinance and the Bill of Right were the compromises between Anti-Federalists who held on to an ontological ancient constitutionalism’s capacity to nourish character; and the Federalist who won the debate with de-ontological modern constitutionalism (American 1787 Constitution), which we Africans are having trouble with for having adopted the modern constitutionalism without the Anti-Federalist’s ontological “ancient constitutional tradition of localism.”[cxlii] Having constitutionally accommodated the moral primordial public within a sub-section of every local government, this is the second thing the 1975-1979 Military Regime should done.

Until, the African democracies could devise their own African variants of localized Northwest Ordinance, which makes possible the nourishing of character through shared purpose, the constitution of the local authorities, and the modified physical environment, there would be no Janus Effects to make polycentricity possible. And this, fortunately, is not a difficult thing to do. As Peter Ekeh taught, we have “the existence of two publics instead of one public, as in the West;” the moral “primordial public” and the colonial and amoral “civic public,” whilst both are kept separate the former is imposed on the latter. For absolute rule, the two publics were created, and the primordial public was transformed into colonial servants. Peter Eketh penned,

“there are two public realms in post-colonial Africa, with different types of moral linkages to the private realm. At one level is the public realm at which the primordial groupings, ties and sentiments, influence and determine the individual’s public behaviour. This is the primordial public because it is closely identified with primordial grouping, sentiment and activities which nevertheless impinge on the public interest. On the other hand, there is a public realm which is historically associated with the colonial administration and which has become identified with popular politics in post-colonial Africa. It is based on civil structures: the military, the civil service, the police, etc. Its chief characteristic is that it has no moral linkages with the private realm. I shall call this the civic public. The civic public in Africa is amoral and lacks the generalized moral imperatives operative in the private realm and in the primordial public.”[cxliii]

This is not something you would find in successful states where there is political stability for economic development. Or do you?

And this “fatal dualism,” [cxliv] as Louis Munoz called it, between the two publics is according to Ekeh, the genesis of “Many of Africa’s political problems.”[cxlv] And this I have sufficiently shown. The first task are the two Afro-democratic and polycentric reforms of (1) decentralization and constitutionalising the local self-government with all the three elements of polycentricism; and (2) the decolonization and the destruction of the two publics of into one single moral and polycentric public. These two Afro-democratic and polycentric reforms are to make possible the nourishing of character by what Ekeh calls moral “primordial public” now without distraction from colonial “parochialisms” like “monoethnic hegemonies,” cultural relativism and ethnic competition for power that manifests as pan-tribalism, prebendalism and prebendal pan-tribalism, which are ironically, as Munoz noted, is caused by “the introduction of universal suffrage” as one of the elements of modernization.”[cxlvi]

By learning from the West how ancient constitutional institutions do teach character, we could rise up to the statement made in Article 27, section 9, of the 2007 African Charter. This section emphasizes the importance of “Harnessing the democratic values of the traditional institutions.” The process of such harnessing, by each political tradition, is clearly stated here.

Following Ostrom’s advice of understanding how the West domesticated the Hobbes Leviathan, we can now begin to deepen our understanding on the three manifestations of civic form; political form; and architectural and urban form. Such thorough understanding is necessary before we move on to Ostrom’s second advice that Africans should discover their our “own history, values, experience and traditions, a path that leads away from the highly centralized state and towards self-governance,’”[cxlvii]

Bottom-Up before Top-Down

These two things, polycentric de-colonization of the two publics and the empowerment of institutions to nourish character, would not only eradicate apathy and create citizenship, but also provide in Steytler’s words the “material conditions in which such policentricity may exist” through a “bottom-up approach to state-building” and through that “the informal structures and institutions of society must be able to claim their place at the table and bargain for and enforce a constitutional compact” to domesticate the Leviathan.

This is the way to ensure that the movement for restructuring is not hijacked by prebendalists and pan-tribalists who are willing instruments of coloniality. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that we cannot think clearly about the forms the constitution would take until the two publics are decolonized and polycentrized. For example, we cannot know whether we should go for a parliamentary system or presidential system; or whether we should go for a four-tiered system (of local government, state, region and federation) or three- tiered system (of local government, state or region and federation); or whether we should go for states or regions as the primal federating units. The actual Afro-democratic reforms must be achieved by representatives of these decolonized and moral public and not prebendalists and pan-tribalists, just as the representatives from the local government rectified the 1979 Draft constitution.

Therefore, top-down political reforms such as federalism or the vertical devolution of power between the local government, the states and the Union and the further entrenchment of the horizontal devolution of power would work best after a successful bottom-up reforms. And in this way an African home-grown system would emerge towards the Nigerian Dream and African renaissance.

Gellar’s Tocquevillian Analytics, is as much the defense of his “Tocquevillian Analytics” as much as a critique of “Samuel P. Huntington’s alternative whose work has greatly influenced the study of democracy in the non-western world.”[cxlviii] Huntington, according to Gellar “accepted the Hobbesian concept of the state which gave the state a monopoly over political authority and unlimited and indivisible authority over those living in a given territory–i.e. the nation-state.” [cxlix] On the other hand, Tocqueville’s study of United States[cl] places ““emphasis on liberty, equality, popular sovereignty, and self-governance as the foundations of democracy”[cli] and holds that “the remedy to the flaws of democracy was more liberty rather than more order.”[clii]

Whilst Huntington holds that democracy is to be built from the top down by national elites ruling a strong state to secure order and tame primordial agitation, Tocqueville sees democracy as “a mechanism for promoting self-governance and preserving liberty” in a bottom-up mechanism from the local government against tyranny. Whilst Huntington holds that, democracy “is based more narrowly on universal suffrage, periodic elections, and multiparty competition,” [cliii] which cultivates tribalism, Tocqueville held that popular sovereignty, and self-governance as the foundations of democracy,” [cliv]

Whilst Huntington placed greater emphasis on the popular election of the top decision makers as the essence of democracy” [clv], Tocqueville “regarded the centralized state as a source of despotism.” Whilst Huntington “saw the centralized state as essential for political modernization,” Tocqueville “advocated more liberty to check despotism.” Whilst Huntington “regarded sub-national group identities and communities based on religion, ethnicity, and kinship as potential dangers to order and political stability and obstacles to political modernization.” [clvi], Tocqueville “promoted self-government and the active participation of citizens in the management of local affairs.”[clvii]

These are the justified, if justifiable reasons for Africans to follow Tocqueville’s path, by themselves for themselves. I am of the opinion that this is the major Achilles’ heel of the 1970s Great Reconstruction. Much of this Huntington’s case for the Leviathan is evident in the political economic reforms, up till now. It is evident in our civic, political, architectural as well as urban forms especially in the federal Capital Territory, Abuja. Today, it’s evident in President Bola Tinubu’s economic neo-liberalism. For Huntington,

“Modern democracy is not simply democracy of the village, the tribe, or the city-state; it is democracy of the nation-state and its emergence is associated with the nation-state.”[clviii]

Though, Huntington recognized “that democratic political institutions and elections existed in Greece and Rome in the ancient world, at the village level, and in many areas of the world where the people elect their tribal chiefs, he dismisses these examples as not relevant in the modern world.” [clix] Interestingly, Obasanjo wrote the same thing in the 1989 Constitution for National Integration and Development. Here Obasanjo states;

“Politics today has gone beyond the practice in the Greek City States where every citizen gathered at the Agora to deliberate. In the same vein, the communal democratic practices of the Tiv and some Igbo societies as well as the checks and balances of the centralized authority systems of the Yoruba and Hausa-Fulani people cannot be the basis of governance today.”[clx]

However, Obasanjo is now greatly transformed. In his, My Watch (vol. 3), he would quote Lord Atkins Adusei’s advice to Nigeria on a bottom-up reforms could be used to dismantle “prebendal pan-tribalist” order –

“This could come in a form of a very broad comprehensive reform to be carried out in all the institutions and sectors of the state: from the security establishment, presidency, judiciary, legislature, civil service, to the private sector. The reform should aim at not only undoing the opportunistic manipulation, neo-patrimonial and vertical power structures that have been constructed by the political elite but also allowing for a more active role by the civil society and the marginalized citizens to ensure greater democratic accountability, good governance, human security, and inclusive development in the country … Who will carry out the reform and how? With so many entrenched interests in the country, it is difficult to think about reforms from top. A reform engineered from the bottom up by the civil society cum the masses might be the only viable option available to kickstart the change badly needed to revitalize the country …. Nigeria’s power holders need to realizes that the country’s position in the world is dependent on what it does first at home, second in West Africa and third in Africa. What it does at home ought to rescue if from the grips of the few home-grown oligarchies and external parasites that have since independence been milking it, paralysing and preventing it from strongly playing its role as a true regional power. Any delay in carrying out a reform will not only make the ‘paper tiger’ and ‘sleeping giant’ stories that have long been associated with the country a reality but will also make the nose-diving decline of the country very hard to reverse”[clxi]

And this bottom-up Afro-democratic reforms is one way to negotiate the bottom-up reforms proposed here by “a friend of Nigeria, Lord Atkins Adusei towards Nigerian African leadership.

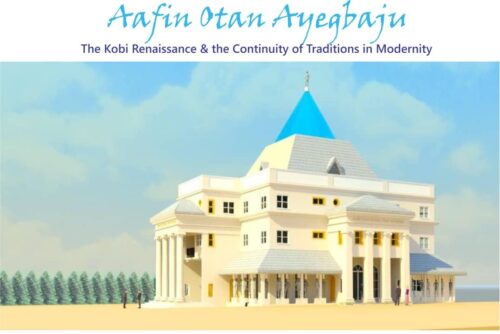

Afin Otan Ayegbaju

Earlier, whilst following the advice given by Munoz and Ogundowole in engaging with the Western civilization towards comprehending “the powerful cultural forces which threaten to overwhelm their indigenous concepts and values” and adopting the “creative approach to the study of Europhilosophical and Eurocultural heritage such that can ensure total de-colonialization,” I have used the two ideas of “polycentricity and de-colonizing the two publics” and “Janus Effects and nourishing character with institutions” in the design and construction of an afin (palace/temple), Afin Otan Ayegbaju in Osun State, Nigeria, I am more than convinced of its other potentialities.

As we have seen how the civic and political forms direct the architectural and urban forms to teach character, architecture is very important in the “the formation of national consciousness and self-assertion.” Zbigniew Dmochowski noted;

“… a building is not an end itself, but rather a means to an end. Which is to satisfy the material and spiritual needs of the people for which it is created. As a natural result, among all the arts architecture is the most firmly linked with human life and reflect it dynamics most faithfully … it now almost universally considered to be elementary means towards the formation of national consciousness and self-assertion. The aim that is sought by these means is to create reference and regard, and finally love, for one’s own tradition. Such true love, Leonardo da Vinci said, is the daughter of true knowledge. The word love is unfortunately seldom used by scholars. But architecture is devised by architects, and no good architecture can originate without respect and love on the part of the society for which it is created-a society which is conscious and proud of its own culture. For love of the human heritage there is just one step to accepting values as a starting point in the creation of modern cultural forms, forms which grow out of, or evolve from, the society’s own cultural past … This statement involves the conception on labour, of human effort, resulting in the creation of new and better human surroundings, both material and spiritual.” ”[clxii]