Protest against economic destruction not treason – Afenifere

September 12, 2024

Toyin Falola to inaugurate new field called African Ancestral Studies (AAS)

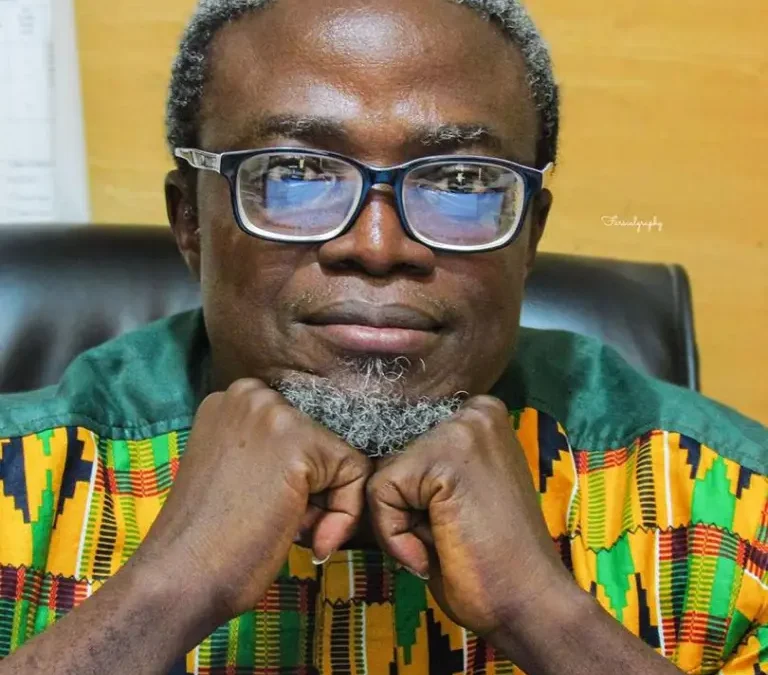

September 17, 2024Adeshina Afolayan teaches philosophy at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He was a Founder’s Fellow at the National Humanities Center, North Carolina. His areas of specialization include African cultural studies, African political philosophy and philosophy of modernity. He is the author of Philosophy and National Development in Nigeria (2018); editor of Auteuring Nollywood (2014) and Identities, Histories and Values in Postcolonial Nigeria (2021); the coeditor of the Palgrave Handbook of African Philosophy (2017), Pentecostalism and Politics in Africa (2018), Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Development in Africa (2020), Pathways to Alternative Epistemologies in Africa (2021), and Global Health, Humanity and the COVID-19 Pandemic (2023).

His current project interrogates the critical engagements between African philosophy and popular music in postcolonial Nigeria. Professor Afolayan spoke with Kolawole Olaiya of Nollywood In Review extensively in Greenville, South Carolina, in December 2023. It was an enlightening dialogue on Nollywood films and philosophy. The issues discussed here should be interest to students and scholars of Nollywood movies.

Nollywood In Review: Thanks for creating time to speak with me. I’ll go straight to the questions: What is philosophy? Why is it relevant in, and to, Nigerian movies?

Adeshina Afolayan: Philosophy is concerned with the critical unraveling and interrogation of our conceptual assumptions and presuppositions around the ideas and beliefs that enable us to make sense of our lives. Philosophy engages humans’ conceptual architecture in order to help us understand the universe and our existence better. Nietzsche insists that we need to always philosophize with a hammer in order to destabilize our beloved idols. And Nollywood—or films generally—constitutes the framework we have developed to re-present our lives, existence and sociocultural dynamics to ourselves. The filmmakers also have the imperative of helping us to defamiliarize the familiar by assisting us to think in ways that re-image and reimagine our belief systems. In Kunle Afolayan’s “The Figurine,” the villagers rebel against Araromire the goddess and her draconian overlordship. That singular act of rebellion borrows from the Yorùbá socio-metaphysical principle: Òrìṣà bí o ò le gbè mí, ṣe mí bí o ti bá mi (Òrìṣà, if you cannot improve my lot, do not worsen it). When philosophy therefore encounters Nollywood, we have a concerted reflexive effort at understanding our lives and social being rather than taking them for granted.

Nollywood in Review: In your book, Auteuring Nollywood (2014), you made a compelling argument on the relevance of philosophy to Nollywood and Nollywood studies. Can you briefly give a recap of that here?

Adeshina Afolayan: That volume was motivated by a fundamental argument—that (African) philosophy and filmmaking on the continent ought to rally around the centrality of vision that is key to the operational dynamics of both. Philosophy unravels around the vision of understanding oneself and one’s place in the universe; and film is methodologically and substantively about seeing. The centrality of vision becomes even more cogent given Africa’s postcolonial predicaments, and the urgent need to ideologically rethink Africa’s place in the world.

Nollywood in Review: In making a case for Kunle Afolayan as an auteur, I am intrigued by the large claim behind auteurism, the claim about the centrality of the director in a production process that involves many critical stakeholders from the producer and screenplay writer to the cinematographer, scriptwriter, and the film stars.

Adeshina Afolayan: Putting Auteuring Nollywood together was a daring endeavor. I took the idea of the “New Nollywood” for granted, and the new cinematic direction taken by Tunde Kelani, Stephanie Okereke-Linus, Kunle Afolayan and many others. And then I took it for granted that the director—these directors—who has a vision also constitute the agential framework for conferring meaning on the film. The director, in other words, is the author as well as the creative core that focuses the intent of the film.

This vision of the director as the author is very intriguing. For instance, it makes a powerful statement that, contrary to Roland Barthes and the rest of the poststructuralist tribe, the postcolonial author is alive and kicking. Rather than avoiding mythologies, as Barthes counsels (in Mythologies), they constitute part of the ideological struggle to rethink and reimagine the African postcolonies. However, with the volume, I was not making a theoretical statement. Rather, I believe I was charting a methodological path for re-viewing Nollywood as a cultural industry for rethinking how we re-tell our narratives, and the role of the film director/filmmaker in that Afrocentric project.

Nollywood In Review: When one thinks about philosophy and film, what readily comes to mind are names of western philosophers like Noel Caroll, Stanley Cavell, Slavoj Žižek, etc. Do we have the equivalents of these in contemporary African philosophy?

Adeshina Afolayan: Unfortunately, there is no contemporary African philosopher I am aware of who has the stature of, say, Gilles Deleuze, the French philosopher, in terms of reflection on the relationship between film and philosophy. Maybe I should gesture at V. Y. Mudimbe and the late Abiola Irele, and their tangential interest in African cultural productions. African philosophers, sadly, are coming very late to the significance of popular culture, and especially Nollywood as not only just avenues for conveying thoughts, but also as possessing the generative and constitutive capacity to extend thought. If philosophy and popular culture constitute modes of, and frameworks for, thinking, then there is no reason why African philosophers should not be engaging with a popular cultural form like film. However, as I have argued in Auteuring Nollywood, contemporary African philosophy suffers from a professional angst, inherited from western philosophy, that conceives it as a second-order discipline with the epistemic warranty to query the epistemic claims of first-order disciplines. This arrogant warrant does not seem to stand a chance in the conversation with popular culture.

Nollywood In Review: Given your musing about the relationship between philosophy and Nollywood, what will be your reflection on the state of Nollywood studies as the site for deepening the relationship between philosophy, film studies and Nollywood?

Adeshina Afolayan: This is a very good question. Nollywood studies provide a significant transdisciplinary site for cultural reflection that is similar to what cultural studies as a disciplinary endeavor does. I envision Nollywood studies as such a site where different disciplines can make contributions to the cultural understanding of Nollywood. John McCall, in “The Pan-Africanism We Have: Nollywood’s Invention of Africa,” already provides one possible template for reflection around the future possibilities of Nollywood. And African philosophers have a lot to add to that reflection.

Nollywood in Review: Some would argue that the traditional world views projected in most Nigerian movies are outdated, although I don’t necessarily subscribe to this notion. In fact, some would argue that some of the world views projected in these movies have contributed to current societal problems. How did Nollywood acquire this reputation? How can philosophy intervene in this regard?

Adeshina Afolayan: I will not like to rehash the discourse around the origin of Nollywood and the terrible disservice that some Nollywood filmmakers had done to the corpus of African cultural memory. And this is due to the commercial motif that motivated many filmmakers. This, for instance, is responsible for the inadequate research that goes into the production of Nollywood films. And the implication is that the filmmakers underestimate the deep sociocultural influence of the portrayal of the traditional worldviews, in terms of epic films, that are misrepresented. However, philosophy should not be seen as having any salvific responsibility in this regard. On the contrary, its responsibility is to participate in the cultural conversation, alongside other African cultural scholars, around the issue of how such imbalances can be redeemed, the conceptual and cinematic challenges of narrating Africa, and what Nollywood and Nollywood studies bring to the table of ideologically re-mythologizing the continent. Thus, an African philosopher must insist on conceptual evaluation, within contextual parameters, as a legitimate dimension of the conversation around what Nollywood is and the extent of its popular and political capacities. The cultural conversation has lots of elements involved. For example, Nollywood has been the subject of many virulent and often uncharitable bashing in the past. And such criticisms do not often take into consideration the complex cultural context, aesthetic limitations, production inadequacies and political economy that attended its emergence. However flawed the conceptual distinction between “old” and “new” Nollywood is, it indicates an evolutionary trajectory that speaks to Nollywood’s internal possibilities to keep reinventing itself.

Nollywood in Review: Most of our film critics are not trained in the aesthetics of film – what they write are a paragraph or two comments on a film. In most cases, the evaluation adds nothing to the meaning or understanding of the movie. I am interested in your thoughts on this and film criticism generally.

Adeshina Afolayan: Well, given the democratization of information through the social media, almost everybody is now a film critic. I am not sure one needs any academic sense of aesthetics to be able to deeply appreciate a film. Film criticism is a hotchpotch of critical opinions about films whose defining objectives can vary from aesthetic formalism to cultural-contextual dynamics. It will be hard to judge what makes a film critic a good critic.

Nollywood in Review: Since we have been exploring popular culture, what is your thought especially about skits? What do you think are the underlying philosophy behind their creation? Is the proliferation of skits healthy for the Nigerian society?

Adeshina Afolayan: Skits, like all other forms of popular culture, mirror and re-present a society’s popular imagination. In a forthcoming book, I have argued that this popular imagination can be framed as a “popular incredible,” a daemonic phenomenon that is essentially ambivalent in its multiple, multiform and multivalent reactions to the Nigerian postcolonial context. To be ambivalent is to be like the Yoruba divinity, Èṣù, and its embodiment of ontological and moral ambiguity. Èṣù constitutes a daemonic figure not only because it mediates between the divine and the human, but essentially because it is ambiguous and contrarian. So, the popular imagination that feeds skits in Nigeria constitutes the originary source for understanding the context and focus of the skits. Nigerian skits, located within the ambivalent context of the popular incredible, are therefore generally vibrant and themed. What is however interesting is how variegated and contrary these skits are, either individually or in comparison. Take Mr. Macaroni’s “Daddy wa-Mummy wa” skit. It is easy to read this skit as promoting a toxic masculinity that poaches on girls, promotes promiscuity, and hence corrupts the youth. It is also easy and legitimate to read it as the eternal frustration of philandering escapades. I particularly love Bovi’s Visa On Arrival, and its multiple themes that intersect patriotism, administrative corruption, workplace excesses, religious extremity, sound administration, citizen-pushback, etc.

Nollywood in Review: Do you believe that film can perform positive social functions?

Adeshina Afolayan: Films have always served as a vehicle for pushing specific sociocultural, ideological and even moral objectives. The Colonial Film Unit produced lots of films and documentaries detailing the colonial achievements. Tunde Kelani is an auteur and Yoruba cultural nationalist. Many Nollywood films have moral imports, from “Afamefuna” to “Oloture.” Socially committed films should not be strange in a postcolony like Nigeria; what would be strange would be an arthouse film that serves an avant-garde audience and aesthetically experimental.

Nollywood in Review: As an avid and critical observer of the industry, you must have noticed especially in the Yoruba sector a recent resurgence of the epic genre. We have films like “JagunJagun” and “Anikulapo.” I am particularly interested in the biopic. “Funmilayo Ramsome Kuti” and “Basorun Gaa” are two distinct ones. What do you think is responsible for this cinematic shift? And what are the possible consequences for cultural understanding?

Adeshina Afolayan: You have asked a critical question that gestures at both the internal evolutionary dynamics of Nollywood and the aesthetic innovation of its filmmakers. Another genre that is making a comeback is the horror film. And this is in spite of the lack of adequate interest in it, compared to the comedy genre. And one good reason for the prominence of comedy is its commercial prospect. From the “Wedding Party” to “A Tribe Called Judah,” comedies have defined the cinematographic direction.

It therefore takes some level of courage to veer off what promises significant profit to make movies that requires extra efforts to break even commercially. And this is all the more so with films with significant historical import. You will agree with me that there is a significant historical deficit in the Gen Z. so many of my students have not heard about Ayinla Omowura. So, there is no motivation to watch Tunde Kelani’s “Ayinla.” The same can be said for “Funmilayo Ransome Kuti.” A cinematic shift, I presume, depends on the possibility of a good story—and the decision, between the producer and the director (or the producer-director) to produce that story. And such a decision contains fundamental pedagogical elements for cultural understanding. Of course, there remains the danger of the auteurial cinematic license, and how that affect our sense of usable history. For instance, the cinematic representation of Funmilayo Ransome Kuti and Basorun Gaa as strong personalities brings home to contemporary reckoning the power relations and asymmetries that the precolonial African societies permit, and the possibilities for their disruption in the service of social change. Thus, in the final analysis, such cinematic license engages and deepens our understanding of the cultural past and what lessons it has for our cultural being-in-the-world. That is one sense to take away from the social media engagement with “Anikulapo” and “Basorun Gaa” on historical veracity.

Nollywood in Review: Thank you, Professor, for this enlightening conversation.

Source: Kola Olaiya