By Olusegun R. Babalola

“With this we are back to the Anti-Federalists’ idea that character must be nourished by institutions. Initiative and optimism are character traits that the Federalist Constitution needs too, not only for political life but for commerce as well.” [i]

- Rose, Carol M., “The Ancient Constitution vs. the Federalist Empire: Antifederalism from the Attack on “Monarchism” to Modern Localism” (1989). Faculty Scholarship Series. 1823. p 105

Most African democracies are only democracies in paper and not in practice and that is why Nico Steytler called them “quasi-democracies” or “illebral-democracies,”[ii] that ironically cannot secure political stability and development, are ruled over by un-domesticated Leviathan. Yet, one of the major political expedients that can be used to domesticate these Leviathans are local authorities (Alexis de Tocqueville) or cities (Leo Strauss) as the schools of enlightened self-interest (Tocqueville)and moral virtues (Strauss). Local authorities can nourish character through the shared purpose (civic form), the constitution (political form), and the modified physical environment (the architectural and urban form) as found in the American 1787 Northwest Ordinance. What follows from here is how the United States domesticated the Leviathan with local authorities amongst other expedients, so that Africans can learn from it.

Ostrom’s advice that African should learn from how the West domesticated the Leviathan,[iii]”as well as look back to their own past to discover in their “own history, values, experience and traditions, a path that leads away from the highly centralized state and towards self-governance,’”[iv] has led me to the recognition of the Janus Effects.

Succinctly, Janus Effects is the process of the complementarity between the old or the ancient and the new or the modern. In this case, our concern is the process by means of which the ontological ancient constitutionalism embodied primarily in the local government, as found primarily in the United States, could shore up the de-ontological and Federalist modern constitutionalism with the cultivation of virtues, through classical moral virtues towards political stability and economic progress. In this case, the major “effects” caused by these dialectics is the new universal political science, established by Alexis de Tocqueville, which are largely based on his observation of democracy in America, but not exclusively devoted to the replication of the American political system. And polycentricity, as conceived by Vincent and Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School, emerged from such effects to primarily defend it. Tocqueville noted clearly that the American manners and laws cannot be imitated but can be fitted to other social conditions.[v]

In the West, and in America in particular, polycentricity is sustained by the ancient or Socratic political philosophy and the Aristotelian political science which survived as what Carol M Rose called the “ancient constitutionalism” [vi] in local authorities. In American democracy, this ancient constitutionalism was inserted by Thomas Jefferson and his committee as the Northwest Ordinance of 1784, 1785 and 1787, in what has come to be known as the Jefferson’s “little republics.” On the other hand, polycentricity emerged through the dialectics between ancient constitutionalism of the Northwest Ordinance and modern constitutionalism of the second American Constitution of 1789, which Tocqueville codified into a new political science. In this way, the modern and polycentric social philosophy is sustained by classical political philosophy.

The focus here is the restoration of the significance of that sustenance with focus on the Northwest Ordinance which is unfortunately downplayed in history. [vii] “Compared to the federal constitution, the average college student today knows almost nothing about the land ordinances of the 1780s.” [viii]

Limit of Polycentricity

The limit of polycentricity is well captured by Andreas Thiel. Polycentric governance, according to Thiel “describes a specific, static structural configuration of governance. It is probably best captured through the original definition of polycentricity by Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren (1961, 831) … This definition aims to provide clues about whether a specific configuration of governance was polycentric. It is not interested in the dynamics of how it emerged, sustains or outlives itself.” [ix] And the “latter, however, may be decisive for performance of governance.”[x] Furthermore, Theil noted “polycentric governance focusses on static structures of governance without giving much emphasis to the way they are enacted. The latter, however, may be decisive for performance of governance.” [xi]

However, the questions still remains – how does this dynamics “emerged, sustains or outlives itself”? How are they enacted? For example, polycentricism cannot solve the problems of ethnic parochialisms. The universal suffrage or the notion of “human right” features in the 2007 African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance[xii] (rectified in 2012) 12 times and several African constitutions. Louis Munoz states that “the introduction of universal suffrage and the principle of citizen participation has the adverse effect of politicizing and therefore consolidating existing parochialisms,”[xiii] that is, of tribalism, and monoethnic hegemonies, prebendalism, but also of the cultural relativism, which frustrate polycentricism itself. Particularly problematic are the problems of pan-tribalism and cultural relativism, which according to Ghai divides the society “on the values of the constitution.”[289] If polycentricity cannot confront these parochialisms, then what can? Why is the universal suffrage the anchor of such parochialisms, in the first place? How did the Western liberal democracy overcome this problem of parochialisms at its foundational stage? The solution to this soluble problem is outside of polycentricism.

There is therefore the need to moving move “up the ladder of abstraction” (using Steytler’s words[xiv]). Steytler had to move up the ladder from polycentricity to Thomas Hobbes’ political philosophy to understand the post-independence continuity of the colonial Leviathan. We have to go even much higher up, to Tocqueville who also operated within Hobbes’ modern political philosophy, and even higher again, to what entirely preceded modern political philosophy of Hobbes, and of Machiavelli. The place to begin is the difference between the ontological ancient constitutionalism and the modern constitutionalism.

The “dynamics of how” polycentricity “emerged, sustains or outlives itself” is well evident in the works of Tocqueville and Leo Strauss, what Thomas L. Pangle called the Tocquivellean-Straussian political science diagnosis, which is a form or echo of “neo-Aristotelian political science.”[xv] This “Straussian-Tocquevillian concern” is “to shore up or repair the pillars of democratic health.”[xvi] And this is concerned with “fanning the embers, within modern liberal democracy, of the older republican citizenship and statecraft.”[xvii] It is in understanding the dialectics between the “modern liberal democracy” and the “older republican citizenship and statecraft” that one encounters the Janus Effects.

Whilst, Tocqueville identified free associations and the “republican self-government of local government” as the heart of the American democracy[xviii] with focus on enlightened self-interest, Strauss would focused more on the classical (Socratic and Aristotelean) understanding of this same phenomenon under the aegis of the “city.” The concern for local self-government, generally in Leo Strauss studies of the classical political philosophy and classical political science is celebrated with that term – “city” – as the school of moral virtues and liberal education, simply.

Between the Old and the New

The place to begin is to drawing the distinction between the old and the new. Alan Gibson made the distinction between the ontological and classical republican political thought and the deontological liberalism, the very basis of the 1789 American Constitution. This was the basic contention between the Anti-Federalists and the Federalists during the creation of that Constitution. According to Gibson,

“classical republican political thought emphasized the ontological priority of the society conceived as an organic whole over the individual and contended that the central purpose of politics was to foster a common understanding of the good life.”[xix]

Furthermore, Gibson noted;

“In the Founders’ conception of a ‘common interest’, however, this concept took on a much more economic meaning — a meaning which does not involve the promotion of a single conception of the good life and thus does not challenge the characterization of their political system as a species of deontological liberalism … the Founders’ conception of a common interest was compatible with individual autonomy and a high degree of scepticism about what constitutes the good life and an unwillingness to have the government foster it.”[xx]

Rose also sheds light on this dualism; the relationship between the ancient constitutionalism and modern constitutionalism. According to Rose “some key components of the Federalists’ plain vanilla constitutional scheme-uniform, large-scale central government on the one hand, and the promotion of commerce on the other.” [xxi] The central troupe are “economic regime of property rights” established “through a legal system that protected the acquisitions and commercial pursuits of the citizens” [xxii] and the necessity of a strong “military force and a standing army.” [xxiii] This is the modern constitutionalism that is different from the older version of constitutionalism, the “ancient constitution.””[xxiv]

Thomas Pangle would also deepen our understanding; “Classical political philosophy is not concerned to rule, but it is concerned to understand, political society—and to share its understanding, in a constructive fashion, with the various political societies and their citizens and rulers. In the pursuit of this civic vocation, classical political theory in the strict or narrow sense takes as its chief task and focus the critical illumination of the highest goals or aspirations that give to political societies their rich and diverse meaningfulness.”[xxv] Unlike the modern political philosophy concerned “concerned about “will to power,”” the classical political philosophy is about “the “will to truth,””[xxvi] “the truth about man’s place in the whole”[xxvii] “of rationally reaffirming the truth of natural right”,[xxviii] “the truth disclosed by reason”,[xxix] – the un-assisted human reason. Furthermore, “classical philosophy ‘‘claimed to teach the truth, and not merely the truth of classical Greece;’’”[xxx] the “final moral truth;”[xxxi] “the truth of the human condition.”[xxxii]

From Leo Strauss we learn, as we shall see that the ontological and classical republican political thought (ancient constitutionalism) accommodates the classic natural rights which imitates nature; and the deontological liberalism (modern constitutionalism) accommodates the modern natural rights which conquers nature. According to Pangle,

“Strauss saw more clearly than anyone the disharmony in the American tradition, between an older, nobler, but less influential classical as well as biblical heritage, and a new, ever more triumphant, permissive, and individualistic order. But precisely for this reason he saw more clearly the distinctive virtues and vices of each component of this uneasy combination.“[xxxiii]

What follows from here is how institutions can nourish character. I would begin with the classical tradition devoted to classic natural right, and then compare that to modern natural right. Having explored both, I would discuss the Janus Effects of enlightened self-interest rightly understood, well documented by Tocqueville.

City and Liberal Education

According to Strauss, the “chief concern of the city must be the virtue of its members and hence liberal education.” [xxxiv] This “city at its best is thus ‘‘liberal,’’ in the classic sense of the term (eleutheros): that is, decisively influenced by ‘‘the morally serious’’ (spoudaioi), the ‘‘gentlemen’’ (kaloikagathoi), who possess the moral and civic virtues aimed at (though by no means automatically produced) by a truly liberating or ‘‘liberal education’’ (paideia eleutheria).”[xxxv] Thus, liberal education is coeval with moral education. In Strauss’ words

“The city is a society which embraces various kinds of smaller and subordinate societies; among these the family or the household is the most important. The city is the most comprehensive and the highest society since it aims at the highest and most comprehensive good at which any society can aim. This highest good is happiness. The highest good of the city is the same as the highest good of the individual. The core of happiness is the practice of virtue and primarily of moral virtue. Since the theoretical life proves to be the most choice worthy for the individual, it follows that at least some analogue of it is the aim also of the city. However this may be, the chief purpose of the city is the noble life and therefore the chief concern of the city must be the virtue of its members and hence liberal education.”

Along this line, “Strauss rearticulates the nerve of the classical theory of politics by beginning with a restatement of the classic contention that the most natural political society is not large, anonymous, and open, or heterogeneous (the ethnos or ‘‘nation’’), but is instead small and closed, or homogeneous: the most natural political society is the polis or city, understood as ‘‘that complete association which corresponds to the natural range of man’s power of knowing and of loving.’’”[xxxvii]

To understand that moral virtue and hence moral education is the chief purpose of the city, one must understand the relationship between a theoretical life of the philosopher lodged in the classic natural right in relations to the practical wisdom of the gentleman and the practical artifice of the architect and the city builder. This is codified here as a two-step transformation of the city of classic natural right.

Two-Step Transformation of the City

It is this understanding of Aristotelian political things that is appropriated by Carroll William Westfall who is also credited with the resuscitation of classical architectural and urban theory, with emphasis on the United States. According to Westfall, “purpose a people have in living together defines the civic form they will find useful, and the civil form defines what is required of the architectural and urban form.”[xxxviii] Thus, three things, according to Westfall, make up the polity, and they are

“a shared purpose, a government they construe in order to exercise power justly while reaching for that purpose, and a physical setting which serves their purposes and facilitates their governing themselves.”[xxxix] “The primal purpose of any polity (no matter its scale) will be to serve the purposes of its citizens while providing justice in their administration of authority, order in the arrangement of their affairs and beauty in the form of the parts and whole of the physical architectural and urban entity housing it.”[xl]

According to this nature of things, architecture and urbanism serve politics as politics serves the shared purpose. Zbiniew Dmochowski also noted

“… a building is not an end itself, but rather a means to an end. Which is to satisfy the material and spiritual needs of the people for which it is created. As a natural result, among all the arts architecture is the most firmly linked with human life and reflect it dynamics most faithfully … it now almost universally considered to be elementary means towards the formation of national consciousness and self-assertion. The aim that is sought by these means is to create reference and regard, and finally love, for one’s own tradition. Such true love, Leonardo da Vinci said, is the daughter of true knowledge. The word love is unfortunately seldom used by scholars. But architecture is devised by architects, and no good architecture can originate without respect and love on the part of the society for which it is created-a society which is conscious and proud of its own culture. For love of the human heritage there is just one step to accepting values as a starting point in the creation of modern cultural forms, forms which grow out of, or evolve from, the society’s own cultural past … This statement involves the conception on labour, of human effort, resulting in the creation of new and better human surroundings, both material and spiritual.” ”[xli]

According to Strauss credited with the “resuscitation of classical republican political theory”[xlii] in our time, “Aristotle held that art is inferior to law or to prudence, that prudence is inferior to theoretical wisdom, and that theoretical wisdom (knowledge of the whole, i.e. of that virtue of which “all things” are a whole) is available is available, he could found political science as an independent disciple among a number of disciples” [xliii] Put in another way, the highest is “theoretical wisdom” [xliv] of the “philosophic way of life” and this made possible the lower “practical wisdom” [xlv] of the gentleman, which is still higher than all other arts, including money making, architecture and city building.

It is that “analogue” of “the theoretical life” which “proves to be the most choice worthy for the individual” that culminate into the civic form of the city. And that analogue makes possible the creation of the civic form of the city, which leads to the political form of the city and finally to the architectural and urban form of the city.

Civic Form of the City

To begin with, one cannot understand the Aristotelian political science before understanding the Socratic political philosophy. Whilst the former focuses on political science and moral education, the latter focuses on classic natural right. Whilst the latter deals with – “ancient utopianism” as “the soul-transforming”[xlvi] as Socrates terms it (Republic 518c–d), and “the most magnificent cure ever devised for every form of political ambition”[xlvii] and through which “the fullest civic expression” is found in “science and liberal education.”[xlviii]

According to Strauss, the ‘‘classic natural right doctrine in its original form,” as the theme of classical political philosophy “if fully developed, is identical with the doctrine of the best regime.’’[xlix] Classic natural right affirms that “there is a standard of right and wrong independent of positive right and higher than positive right: a standard with reference to which we are able to judge of positive right.’’[l] And at the center of this is virtue, the philosophic virtue of a contemplative life. These are the good old virtues; the existence of natural law (wisdom/insight), political autonomy (courage), political responsibility (temperance or moderation), and the equality of opportunity for all citizens (justice).

But there exist then an “insoluble tensions” between the gentlemen’s “civic or moral virtues and the (ultimately higher) philosophic virtues”[li] This is because “for most men at all times and for all men most of the time, reverence for one’s heritage, for tradition’’ which are “essentially particularistic.””[lii] This is the case since ‘‘every political society that ever has been or ever will be rests on a particular fundamental opinion which cannot be replaced by knowledge and hence is of necessity a particular or particularistic society’’[liii]

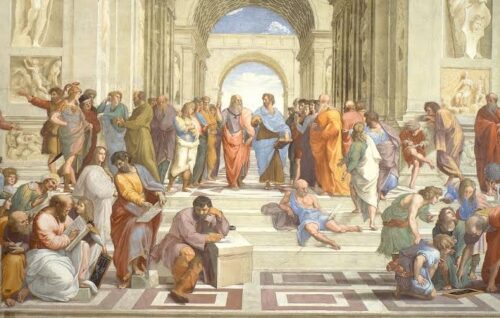

But whilst Socratic political philosophy held that classic natural right transcends the political society, Aristotle argued that such transcending “cannot be the right natural to man, who is by nature a political animal.”[liv] For Aristotle, “natural right is a part of political right”, though natural right exists “outside the city or prior to the city.” [lv] “What Aristotle suggests is that the most fully developed form of natural right is that which obtains among fellow-citizens; only among fellow-citizens do the relations which are the subject matter of right or justice reach their greatest density and, indeed, their full growth.”[lvi] This difference is evident in Raphael’s fresco whilst Aristotle points down as Plato points up.

Though Aristotle’s moral virtue “is a kind of halfway house between” Plato’s “political or vulgar virtue which is in the service of bodily well-being (of self-preservation or peace) and genuine virtue” which “animates only the philosophers as philosophers,”[lvii] Aristotle’s “man of moral virtue or “good man” who is the perfect gentleman and the “good man” … is just and temperate” and is not “like the members of the lowest class in Plato’s Republic.”[lviii] It is this “moral virtues and perfection” that is based on “practical wisdom or prudence,”[lix] the “man’s second natural end, his social life,”[lx] whilst the philosophical virtue that is based on “theoretical understanding or philosophy” as the “highest end of man by nature.”[lxi]

Moral virtue “shows that the city points beyond itself but it does not reveal clearly that toward which it points, namely, the life devoted to philosophy.”[lxii] Because Aristotle held that art is inferior to law or to prudence, that prudence is inferior to theoretical wisdom, and that theoretical wisdom (knowledge of the whole, i.e. of that virtue of which “all things” are a whole) is available, he could found political science as an independent disciple among a number of disciples in such a way that political science preserves the perspective of the citizen or statesman or that it is the fully conscious form of the “common sense” understanding of political things.”[lxiii]

These gentlemen – “well-bred men who simply always do the right and proper thing” without shame are to directly enrich the political societies.”[lxiv] “According to Aristotle it is moral virtue that supplies the sound principles of action, the just and noble ends, as actually desired; these ends come to sight only to the morally good man; prudence seeks the means to these ends.”[lxv] The “gentleman affected by philosophy” [lxvi] pursues “moral virtue that supplies the sound principles of action, the just and noble ends”[lxvii] with prudence. And the “highest form of prudence is the legislative art which is the architectonic art, the art of arts, because it deals with the whole human good in the most comprehensive manner.” [lxviii] Carroll W. Westfall, who would also resuscitation of classical architectural and urban theory, also stated that “prudence is the chief political virtue”[lxix]

Furthermore, practical wisdom which is concerned with “the whole human good in the most comprehensive manner” is higher than other arts like “money making”[lxx] or city building and architecture that are concerned “with a partial good,”[lxxi] as well as those lesser arts that are affected and modified by the gentleman’s moral virtue. Put succinctly, moral virtue as the shared purpose of the city, the prudence of the legislative art of the city directed at moral virtue, and the architecture within, as well as the physical city affected by prudence towards moral virtues, are the core basis of the moral education of the city, by means of which a city can nourish character. This city “is the locus of that materially self-sufficient living together that most truly suits human nature.”[lxxii]

Political Form of the City

Politeia according to the classics “means the way of life of a society rather than its constitution” and that “way of life of a community as essentially determined by its “form of government.””[lxxiii]Politeia could then be translated as the “regime.”[lxxiv] “The politeia is” therefore “more fundamental than any laws; it is the source of all laws. The politeia is rather the factual distribution of power within the community than what constitutional law stipulates in regard to political power. The politeia may be defined by laws, but it need not be.” [lxxv] It is primarily the factual “arrangement” of human beings in regard to political power that is meant by politeia.”[lxxvi] With respect to the classical republican theory, Aristotle established the scientific basis of understanding the “form of the city” or the Politeia or the “regime” which further reveals the in-extirpable root of international conflict in the political insolubility of the problem of justice”[lxxvii] among cities.

The “classic natural right doctrine in its original form, if fully developed, is identical with the doctrine of the best regime.’’[lxxviii] And the ‘‘best regime simply’’—would “be dedicated to the maximum possible human fulfillment” but is not a “practical goal” [lxxix] As a result, the “The classics devised or recommended various institutions which appeared to be conducive to the rule of the best.” [lxxx] As a result, according to Strauss,

“one may say that it is characteristic of the classic natural right teaching to culminate in a two fold answer to the question of the best regime: the simply best regime would be the absolute rule of the wise; the practically best regime is the rule, under law, of gentlemen, or the mixed regime.”[lxxxi]

According to Pangle, “In the pursuit of this civic vocation, classical political theory in the strict or narrow sense takes as its chief task and focus the critical illumination of the highest goals or aspirations that give to political societies their rich and diverse meaningfulness.”[lxxxii]

“At the heart of that wisdom” provided by “from Aristotelian political science “is the focus on the regime as the supreme political phenomenon, as the core of a society’s self-definition and hence its very existence as the distinct society that it is.“[lxxxiii] The notion of the regime implies that “the character of a given city becomes clear to us only if we know of which kind of men its preponderant part consists, i.e. to what end these men are dedicated.”[lxxxiv] we could compare the republican regime at Washington D.C. to the theocratic regime at the Vatican City and the mixed government regime of the United Kingdom.

“In the massive foreground of Strauss’s lifework” according to Pangle, “stands his resuscitation of classical republican political theory, understood as emanating from the intellectual revolution effected in and by Socratic political philosophy. It is here that Strauss finds the standpoint for a searching and critical, while sympathetic and admiring, appraisal of our contemporary liberal democracy.”[lxxxv] The application of this classical republican political theory, and hence, the application of the Aristotelian political science and liberal education” is therefore “the fullest civic expression of Socratic philosophy.”[lxxxvi]

Architectural Form of the City

Westfall would appropriate the Vitruvian trilogy; commodity, firmness and beauty[lxxxvii] as the basis of his dialectical discourse on how architecture and urbanism teach character. Westfall would therefore examine this Vitruvian trilogy as sources of knowledge,[lxxxviii] that can nourish character. Commodity is provided by the political purposes that are affected by classic natural right; responsibility, freedom, natural law and equality of opportunity for all citizens. Westfall probably writes esoterically rather than ambiguously because he did not use the term “classic natural right,” but simply “natural right.” However, his intentions are clear. He is understandably, reluctant in making explicit difference between classic natural right and modern natural rights, though his expressions on each are un-mistakably clear.

Classic natural right is incorporated into politics through the constitution and laws of the politeia organizing political activities dedicated to political purposes. Within his framework of four activities, primary, religious, political and civic activities, are defined based on political purposes – “on how buildings serve politics.”[lxxxix] While the first three are universal, the fourth is particular. However, I have here modified Westfall’s religious activities into “moral activities” which accommodates the permanent problem, the tension and competition between the philosophic and the religious activities on the morality of the city. This, Strauss described as the theologico-political problem. The reason for this is also very explicit in Westfall’s gloss over the theologico-political problem (pages 69-70). By comparing the philosophical United States to the theological Vatican City, we have already been introduced to this problem.

Six building types (or so), with specific gerunds, are derived from the three activities, two gerunds for each; primary activities (dwelling and trading), political activities (aspiring and exercising authority) and moral activities (venerating and celebrating). Each comes with its specific natural geometry. These are universal types made possible conventionally via utilitarian components that serve the functional aspect of commodity – building types.[xc] For example, the St. Peters Basilica in the Vatican combines the “venerating” and “celebrating” as the United States Capitol building is clearly a composite of a “venerating” flanked by two “aspiring” spaces with the facades associated with the fronts of “celebrating” according to the Western classical traditions.

On firmness there are three structural types (or so) of structural type (building a wall, turning an arch, raising a colonnade), and five artifice’s materials components (piece, element, motif, covering and structural component). These also manifest conventionally as material components serve the structural types. On beauty, Westfall would resuscitate Alberti’s definition of beauty. Beauty is derived from commodity and firmness based on imitation of nature; hierarchical distinctions between assemblage of buildings serving different political purposes of the constitution; the rules of congruity as a mean between excess and deficiency; embellishment (decoration and ornament); and the four aspects of congruity (number, finishing/proportions, collocation and congruity itself).

As utilitarian components and material components serve the commodity and stability respectively, so do decoration (function/decorum) and ornament (structure) also serve beauty.[xci] And the most important ornament of the regime is used on the most important building at the most central part of the city, teaching morals based on the character of the politiea or regimeb- pointing to what the regime looks up to. The hierarchical distinctions between assemblage of buildings, with hierarchical placement of decorations and ornaments, whilst serving different political purposes of the constitution all culminate on this most important building. Good examples are the Statue of Freedom on the venerating dome of the United States Capitol Building in Washington D.C., and the Crucifix on the venerating dome of the St. Peters Basilica in the Vatican City. Both teach what the regime looks up to. This beauty that teaches “is in the building, not (merely) in the eyes of the beholder.”[xcii]

Urban Form of the City

Within the city proper, there are other elements as the building components (tower; platform; wall, colonnade or arcade; gateway; and parterre, greensward and basket), all coordinated via architectonic means (axes, open areas like squares, reserved strips like roads, relationship between things and hierarchic differentiation) culminating in the visible, conventional and communicative (epistemological) urban pattern of the particular regime, with the most important building at the center. All these are combined and disposed “homomorphically within a homogeneous space in order that the rational connection between the civic and the urban can be put to the service of citizens,”[xciii] to teach moral virtue and mold character.

The connected network of open spaces like streets, reserved strips or axes, signifying political freedom, define enclosed spaces of private and public enterprises, as well as private homes anchoring equal opportunities as other hierarchical spaces of political covenant, where the wise rule and especially where what the regime looks up to is placed, which demands political responsibility. The city as a communicative composition of void and solid, public and private buildings, building components within the homogeneous space are charged with the political content, political hierarchy, all coherently scaled for citizen’s habitation and comprehension. If the urbs communicates clearly the politiea of the city, then man can understand what he “ought” to do to achieve the best society possible in that constitution. [xciv]

Two good examples of axis are; the alignment of the US Capitol, the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Monument in the Washington D.C.; and St. Peters Basilica and the Egyptian obelisk, now Vatican Obelisk capped with a bronze cross. Other good examples are the “Bernini’s great piazza in front of St Peter’s” [299] and the McMillan Commission’s National Mall in front of the US Capitol based on homomorphic design by Pierre Charlse L’Enfant.

These are first given form by the politeia before architects and artists are commissioned. they point to the politeia before pointing to the laws or constitutions – they point to the de facto before the de jure. Whilst the intangible political form of the city derived from abstract ideas is very elusive and difficult to communicate to the citizenry, the physical urban form which accommodates both the politeia and variant of moral virtues, which Westfall calls ‘urbs,’ is not. And because the politeia or political form of the city created with the principle of classic natural right could speak through the architectural and urban form of the city, the urban form of the city could nourish virtue and character.

Such cities are not dump like most modernist African capitals based on positive law and not natural law. It would be hard to find civic responsibility there, and freedom would be synonymous to anarchy due to utter absence of integrity.

“Like its neighbors and its predecessors, the civic buildings running back to the ones crowning Pericles’ Acropolis, it shows that a building is an imitation of the pattern of nature resident on the site in the form of the political purposes that are to be served and the normative standards guiding the use of materials put into the service of architecture to accommodate those purposes.”[xcv] According to Westfall,

“Just as there is only one politics (the art of living together in order to perfect the nature of each individual) so too is there only one architecture (the art of building that serves that politics).”[xcvi]

The architectural and urban forms, conceived as explained above is in accordance to the ‘‘classic natural right doctrine in its original form,” and the theme of classical political philosophy “if fully developed, is identical with the doctrine of the best regime.’’[xcvii] The implication of the Socratic political philosophy as the ‘‘gadfly’’ stings to the city is the moral education – that Strauss penned “it is ‘‘not sufficient for everyone to obey and to listen to the Divine message of the City of Righteousness, the Faithful City’’: in order to understand that message as clearly and as fully as is humanly possible, one must also consider to what extent man could discern the outlines of that City if left to himself, to the proper exercise of his own powers.’’[xcviii]

Modern Constitutionalism

“Strauss summarizes the Enlightenment philosophers’ statements of purpose, using their own phraseology, as follows: ‘‘philosophy or science was no longer to be understood as essentially contemplative and proud but as active and charitable’’; ‘‘it was to enable man to become the master and owner of nature through the intellectual conquest of nature.’’”[xcix] (Italics is mine) According to Strauss”

“humanity is no longer to be conceived in terms of a hierarchy of spiritual needs directed by and toward a natural perfection or order of rank within the soul. Instead, what is to be regarded as natural to the human species are animal passions, the strongest of which are the drive for security and the drive for superiority or control, given scope in a uniquely human plasticity that is shapeable and hence shaped by reason, which can figure out an integration of the passions. Mankind can and should devise for itself artificial structures of existence that allow the most gratifying expression of its passions, rendered human through conscious and unconscious construction and reconstruction.”“[c]

The switch from the ontological ancient constitutionalism to the de-ontological modern constitutionalism began with Machiavelli and then followed by others, Bacon, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, Locke, Montesquieu.”[ci] On this switch, Laurence Bems tells us;

“Nothing which mortals make, says Hobbes, can be immortal. Yet with the help of a very able architect, commonwealths can be so constructed as to prevent their perishing from internal disorders. Hobbes describes those forces in the nature of man which have always tended toward the dissolution of peace and civil order. Yet those forces are not to be counteracted by way of moral reform, by appeals to what had been regarded as the nobler part of man’s nature. Hobbes appeals instead to enlightened self-interest and, on the basis of knowledge and manipulation of the mechanism of the passions, relies on the devising of the right kinds of institutions. There was no need for him, as there was for Aristotle, to distinguish the kinds and levels of peoples in order to determine what kind of government is suitable for each. He aimed at devising a scheme of government which was to be right for all times, peoples, and places. By building his edifice upon the lowest common denominator of human motivation, he could expect it to stand firm anywhere and everywhere.” [cii]

Pangle also noted that the modern natural right or the “Lockean doctrine of natural right—of the natural (universal and fixed) rights finds its way into the regime of the United States. This is found in the Declaration of Independence’s proclamation of the ‘‘self-evident truths’’ that ‘‘all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.’’[ciii] “Not only do these men of action speak for themselves, but they point us with some explicitness to their philosophic teachers, above all (though by no means exclusively) Locke and Montesquieu.”[civ]

Janus Effects; The Compromise between Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The first American Constitution, the Article of Confederation, was based on civilizational and ancient constitutionalism which accommodated “existence of many centers for decision making” and the “existence of a spontaneous social order” but lacked “existence of a single system of rules.” As a result, it could only provide for a very weak Union.

The concern for the small self-governing community as the school of republican virtue was one of the themes pushed by the Anti-Federalists during the founding of the United States. This, which Gibson called ontological “classical republican political thought” is referred to by Carol M Rose as Anti-federalist’s ancient constitutionalism.[cv] This notion of small self-governing community as the school of and for republican virtue is referred to by Rose as Anti-federalist’s ancient constitutionalism.[cvi] Strauss clinically noted that during this debate ‘‘the authors of the Federalist Papers signed themselves ‘Publius’: republicanism points back to classical antiquity and therefore also to classical political philosophy.’’”[cvii](75-6) This was to feign the ancient republican virtue. The Antifederalists were not moved by the de-ontological constitutionalism. Anti-Federalists objected that the “necessary republican virtue,” the “republican genius of the people” is taken for granted[cviii] and demanded for the Bill of Rights.

The constitution was eventually based on the de-ontological constitutionalism of “the regime of individual liberty and indirect majoritarian rule elaborated in the predominantly (though not exclusively) Lockean natural rights political theory and Montesquieuian constitutionalism of the Founders,”[cix] and the Bill of Rights was one side of the subsequent compromise. These was an earlier compromise.

The most important compromise to me appear to be that whilst the new 1789 Constitution, based more on modern constitutionalism, was introduced to secure the second element – “existence of a single system of rules” towards a stronger government, the local government principles based on civilizational and ancient constitutionalism with accommodation for what could be called the Aristoteliean moral virtues, were at first preserved within a federal structure through the Northwest Ordinances of 1787, and finally secured by the 1789 Bill of Right (ratified in 1791) – the first 10 Amendments to the 1789 Constitution.

The irony is that 1787 ordinance lacked a strong central government to implement it and the U.S. federal government formed in 1789 based on modern constitutionalism was able to do that. Whilst the Northwest Ordinances created the republican and an ontological basis for bottom-up reforms based on ancient constitutionalism; the new 1787 Constitution provided the liberal and a de-ontological basis for top-down reforms. Whilst the ancient constitutionalism in the grassroot, now protected by the Bill of Right, became the haven of ontological classic natural rights that shores up the federal and de-ontological modern natural rights of the Federalist Constitution, the latter also secured a strong basis for federalism to implement the former. That is the Janus Effects.

The 1789 “vanilla” Constitution, the 1789 Bill of Right and the earlier Northwest Ordinances of 1787 which according to Sheldon Gellar made “Property rights systems in America favored more egalitarian distribution of land than the primogeniture system prevailing in Europe”[cx] were the great innovations of the era of the great debate between the Federalists and the Anti-federalists. These led to a binary complementarity, the Janus Effects, by means of which both the old and the new are in harmony, and in this case, the ancient constitutionalism shores up the lifeless modern constitutionalism with virtue and character.

Thomas Jefferson, Local Government and the Northwest Ordinance

The precedents set by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established the character of the local government, the establishment of the new states and the relationship between the States and the Union. It does this by establishing the basis for the civic form of the city, the political form of the city and the urban form of the city.

The Ordinance “provided for freedom of religion, made available writs of habeas corpus and jury trials, and recognized other rights that later appeared in the Bill of Rights; it encouraged the development of schools, prohibited slavery while requiring fugitive slaves to be returned to their owners, and laid out a process by which the territory would be divided into states which could then enter the union.”[cxi] Secondly, it defined the local government – the 36-square-mile townships – as a republican direct democracy and the smallest unit of government. And thirdly, it created the “legal guidelines directing the nation’s physical and political growth. The ordinances were as fundamental as was the federal constitution itself.” [cxii]

In 1787, there “was a substantial amount of communication between the Constitutional Convention devoted to modern constitutionalism and the Congress of the ancient constitutional Article of Confederation working on the Northwest Ordinance [cxiii] which were going on concurrently. Douglass C. North & Andrew R. Rutten argued that certain compromises were made between them. [cxiv] And I argue here that the tacit recognition of classic natural right based on the ancient constitutionalism by the Ordinance was one of them.

And before the emergence of the new Constitution, the far-seeing Thomas Jefferson (supported by James Madison,[cxv] George Washington[cxvi] and James Monroe.[cxvii] ) had started pushing for what came to be known as the Northwest Ordinances of 1787 since1784.

This prudence or the practical wisdom (mentioned above) dedicated to teaching citizens moral education, as Westfall would argue, is not unknown to Thomas Jefferson and his committee that devised the 1784 Northwest Ordinance which was latter modified in 1785 and 1787. According to Westfall, “the political, surveying and settlement system embodied in the universal grid system of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787,”[cxviii] for homomorphic architectural forms and urban forms. Westfall speaks of Jefferson as

“a political man committed to thinking of the land as a place where the farms of patriots would spring up, provided the essential material for the two parts of the Northwest Ordinance, one defining how the land would be measured to produce an urbs, the other specifying how the now measured land would form states (polities) and join on an equal footing with the other states comprising the union.”[cxix]

Yet the same Jefferson had penned Declaration of Independence which contains modern natural right. He had supported James Madison, the author of the first draft of the 1789 Constitution and the subsequent the Bill of Right as a compromise between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalist. Yet, Westfall speaks of “Thomas Jefferson, an architect” and urban designer. He designed the temple fronts of Virginia Capitol in Richmond that was imitated in the Capitol building;[cxx] the University of Virginia with classical civic form, political form and urban;[cxxi] his own private residences like Monticello and other buildings; most particularly, he made a significant design contribution to L’Enfant’s design for Washington.[cxxii]

Interestingly, Strauss’s famous 1964 book The City and Man, a brilliant attempt to liberating modern political philosophy from ideology with classical political philosophy, is based on a set of lectures he gave at the Mr. Jefferson’s University of Virginia in 1962.

Janus Effects and other Effects

Aside from shoring up virtue and character, the American “Founding exhibits unsolved and even insoluble problems that keep the regime in troubled motion, and that surface at periods of great tension or struggle over the meaning of the regime.”[cxxiii] “The Founding is of course not the end of the story. But the Founding sets the horizon within which move subsequent developments—even when they verge on ‘‘re-foundings’’ (the Jeffersonian and Jacksonian movements, the struggles over slavery and race; the response to the Great Depression, the Cold War).” (105)

For example, the ancient constitutionalism evident in the Northwest Ordinance, which is at the heart of what would be called Jefferson’s little republic was in fact the precursor of the Anti-Federalists’ localism and ancient constitutionalism and the compromise of the Bill of Right, as well as the very basis of the opposition group – the Jeffersonian Party. The Jeffersonian Party – which centered around Jefferson and Madison, the same author of the first draft of the Bill of Right. And thus began the multi-party system.

This “unsolved and even insoluble problems” was what led to multi-party system and kept them moving and transforming. Multi-party system did not fall from the sky. Interestingly, it was the same Thomas Jefferson and Madison that established the practice of multi-party system through their vibrant opposition politics.

Janus Effects also led to the 1960s debate between the advocates of the gargantuan and the advocates of polycentricity and the further development of polycentricity by Vincent Ostrom and the Bloomberg School.

In short, one cannot establish and nourish a polycentric governance within modern constitutionalism as such until when one has operatively entrenched that “republican genius” or the moral virtue of the people secure by the ontological and ancient constitutionalism. Thus, “strengthening and building the polycentric nature” is the same as activating or nurturing those virtues of ancient constitutionalism, whether, such virtue is republican or the moral virtues of a mixed regime made up of the monarchy, aristocracy and the people.

Alexis de Tocqueville Codified the Janus Effects

Like Hobbes, as Marvin Zetterbaum stated, “Tocqueville rejects the classical contention that justice has as its theme in the pursuit of human excellence. In common with modern political philosophers, he holds that justice is derivative from natural rights.” [cxxiv] Zetterbaum noted that this

“reveals Tocqueville’s fundamental agreement with the presuppositions of modern political thought; despite apparent departures, Tocqueville follows in the tradition originating with Machiavelli and continued in the natural right teaching of Hobbes. Tocqueville follows in the tradition originating with Machiavelli and continued in the natural right teaching of Hobbes. The political problem of man is solved by lowering one’s standards— the doctrine of self-interest rightly understood does not aim at lofty objects.” [cxxv]

To be sure, I would explore Tocqueville based on the same themes that I have explored the classical tradition.

Tocqueville’s Old and New

Tocqueville would simply contrast the “old regime” of “an aristocratic state of society” to the new “democratic regimes.” For Tocqueville, the cause is “That social condition which is the moving principle of democratic regimes is the condition of equality … this is the “fundamental fact from which all others seem to be derived.”[cxxvi]””[cxxvii] There is a difference between equality of conditions which has taken roots in America and in-equality of conditions[cxxviii] as “the social state of the old regime, either of France or of feudal Europe generally.”[cxxix] To the “old regime” “Tocqueville ascribes to an aristocratic state of society: a certain elevation of mind and scorn of worldly advantages, strong convictions and honorable devotedness, refined habits and embellished manners, the cultivation of the arts and of theoretical sciences, a love of poetry, beauty, and glory, the capacity to carry on great enterprises of enduring worth.” [cxxx]

“The characteristic feature of democratic society is its atomism.” [cxxxi] Men confront each other as equals, each independent, each impotent.” [cxxxii] “According to Tocqueville, the key to the atomistic quality of democratic ages lies in the diffusion of “individualism,”.” [cxxxiii] “Wholly absorbed in the contemplation of this universe, the individual loses sight of that greater universe, society at large.” [cxxxiv]“ When individualism is linked with equality of conditions, an insatiable thirst develops for the material comforts of this world. In a society shorn of the traditional restraints and obligations—to country, to lords, to church—“where the materially comfortable nobility and ruling class made way for the cultivation of the higher faculties ”men strive eagerly to gratify their immediately felt and immediately intelligible desires to improve their conditions of life.”[cxxxv]

Tocqueville’s Two Step Transformation

“In Democracy in America, Tocqueville identified mores (manners and customs, habits of the heart and mind); laws, (institutional arrangements); and environmental factors (geography, topography, climate) as the three main factors shaping American democracy.”[cxxxvi] The laws and manners are the basis of American greatness, but Tocqueville “pointed to moeurs as the most significant factor explaining the success of American democracy. The term embraced American values, morality, ideas, attitudes, and customs.”[cxxxvii] Tocqueville noted that “The importance of manners is a common truth to which study and experience incessantly direct our attention. It may be regarded as a central point in the range of human observation, and the common termination of all inquiry.”[cxxxviii] The physical circumstances Westfall speaks of is the architectural and urban modification of the physical environment derived from manners in the service of laws. However, as we shall see, Tocqueville’s thorough analysis of democracy in America also noted how mores and laws also affect the built environment.

On manners the most important of “the three main factors shaping American democracy”[cxxxix] is the Enlightened self-interest rightly understood defines the democratic morals that Tocqueville found in America. As far as virtue is concerned, the heart of the matter for Tocqueville is the principle of self-interest rightly understood, which he severally called manners. Unlike the wanning and “subsequent aristocratic age of the feudal system and the social conditions of in-equality” when “many were motivated by the appeals of self-sacrifice and virtue” in the democratic age “conditions of equality”[cxl] Tocqueville affirms, that “private interest” is “the only immutable point in the human heart,”[cxli] and “becomes the principal if not the only spring of human action.”[cxlii] “

Civic Form

The first place to begin the understanding of Tocqueville is his disgust for both despotism and apathy and his appreciation of how America resolved this issue. In Democracy in America, these two evils – anarchy and despotism, the twin enemies of liberal democracy,[cxliii] are the perpetual concern of Tocqueville. And they are lucked between the lines of every page. In Europe, and especially in early 19th Century France, he noted that “a people might organize a stupendous tyranny in the community, at the very time when they were baffling the authority of the nobility and braving the power of all kings.”[cxliv] “They had sought to be free in order to make themselves equal; but in proportion as equality was more established by the aid of freedom, freedom itself was thereby rendered of more difficult attainment.”[cxlv] He would use this to compare the United States and France in the 19TH Century to explain the French in ability to negotiate change.[cxlvi] “Tocqueville’s purpose in the Democracy is to show men how they might be both equal and free.”[cxlvii] According to Tocqueville;

“It cannot be absolutely or generally affirmed that the greatest danger of the present age is license or tyranny, anarchy or despotism. Both are equally to be feared; and the one may as easily proceed as the other from the selfsame cause, namely, that “general apathy,” which is the consequence of what I have termed “individualism”: it is because this apathy exists, that the executive government, having mustered a few troops, is able to commit acts of oppression one day, and the next day a party, which has mustered some thirty men in its ranks, can also commit acts of oppression. Neither one nor the other can found anything to last; and the causes which enable them to succeed easily, prevent them from succeeding long: they rise because nothing opposes them, and they sink because nothing supports them. The proper object therefore of our most strenuous resistance, is far less either anarchy or despotism than the apathy which may almost indifferently beget either the one or the other.” [cxlviii]

“Any attempt to temper democracy with principles or practices from a regime alien to it is doomed to failure; not even a despot can rule under the democratic principle without making his obeisance to equality. Thus, Tocqueville warns his contemporaries that the task is not one of reconstructing aristocratic society, but of making liberty proceed out of the democratic state of society and of working out “that species of greatness and happiness” appropriate to equality of conditions.” [cxlix]

“Providence,” he tells us, “has not created mankind entirely independent or entirely free. It is true that around every man a fatal circle is traced beyond which he cannot pass; but within the wide verge of that circle he is powerful and free.”[cl] Tocqueville’s work appears as an admonition to men to make the best of the lot awarded them by God—men cannot determine whether conditions will or will not be equal, but theirs is the responsibility whether equality will lead to wretchedness or to greatness, to slavery or to freedom … To accomplish this end, Tocqueville calls for a “new science of politics,” one adequate to the novel conditions occasioned by the triumph of equality.”[cli]

“Faithful to the requirements of equality, Tocqueville appeals to the self-regarding instincts of man and strives to erect upon this basis a species of public morality and of patriotism: he would make men virtuous by teaching them that what is right is also useful.” [clii] The foundation of the public or social order rests upon enlightened selfishness: each individual accepts the view that “man serves himself in serving his fellow creatures and that his private interest is to do good.” [cliii] and that men “must come to see the desirability of postponing the immediate gratification of their desires in the expectation of a more certain or greater degree of satisfaction at a later time, an expectation arising from the contribution of the common welfare to their own well-being.”[cliv]

And this “self-interest be rightly understood” is “is understood primarily in an economic sense—it is a concern with the most immediate, tangible, material signs of a man’s well-being.” [clv] This economic sense, what Strauss called “the “art of arts; money making,”[clvi] which is like every “every art” is concerned “with a partial good”[clvii] and thus beneath the “highest form of prudence” which “is the legislative art which is the architectonic art, the art of arts, because it deals with the whole human good in the most comprehensive manner.” [clviii] This economic sense is compatible with this modern constitutionalism.

Tocqueville admits it “is not a lofty one, but it is clear and sure. It does not aim at mighty objects, but attains without exertion all those at which it aims.” [clix] “Out of an enlightened regard for one’s own material welfare, a good other than an economic one will emerge: patriotism or public spiritedness is the by-product arising from the intelligent pursuit of one’s own interest.” [clx] Along this line, Tocqueville advocated liberal education directed at making the people rise above themselves. In democracy, education is needed to defend independence. Intelligence, knowledge and art are needed to maintain secondary powers to defend independence regardless of individual weakness, through free associations against tyranny without destroying the public order.[clxi] Tocqueville’s primal object is the need for people to rise above themselves.[clxii] He was concerned about “the community prepared to make great sacrifices with little difficulty?”[clxiii] His book, it itself liberal education.

And interest rightly understood is supported by and compatible with otherworldly support; religion and also by extension philosophy, though the latter is wanning in influence.[clxiv] For Tocqueville the general ideas about immortality, “God and the human soul are therefore preservers of human freedom,” [clxv] whether it is a religion even “false and very absurd” [clxvi] religions or “supersensual and immortal principle.” [clxvii] Religion “is invoked not only to justify the supreme sacrifice, but also to combat both the individualism and materialism of democratic ages.” [clxviii] ““Tocqueville affirms that freedom is impossible without morality, and morality impossible without religion. Religion supplies those “dogmatic beliefs” which are the cement of society, beliefs about the nature of God, the soul, and of men’s obligations to each other and to that greater whole, the state, of which they are a part. This is especially necessary in times of extreme individualism.” [clxix]

Tocqueville commended “Socrates and his followers” of their “the doctrines of a supersensual philosophy” on the affirmation that “the soul has nothing in common with the body, and survives it” [clxx] against “the passion for physical gratifications.”[clxxi] Tocqueville celebrated the “doctrine of metempsychosis” [clxxii] which is found in the last part of Plato’s Republic (Book 10, Section 620) and the importance of “supersensual and immortal principle” [clxxiii] to “bring men back to spiritual opinions” [clxxiv] from crash materialism – the “taste for physical gratification” [clxxv] to which democracies are susceptible to.

Political Form

“The fundamental paradox of democracy, as Tocqueville understands it, is that equality of conditions is compatible with tyranny as well as with freedom. A species of equality, at least, can coexist with the greatest inequality.”[clxxvi] “The passion of men of democratic communities for equality is ardent, insatiable, incessant, invincible; they call for equality in freedom, and if they cannot obtain that, they still call for equality in slavery.” [clxxvii] As a result of equality, “it is easier to establish an absolute and despotic government amongst a people in which the conditions of society are equal, than amongst any other” and would oppress them and “strip each of them of several of the highest qualities of humanity.”[clxxviii]

Tocqueville was particularly critical of despotism. Unfortunately, the “wisest” are often alarmed by the anarchy rather than the despotism.[clxxix] Equality thus prepares man to surrender his freedom to safeguard equality itself.” [clxxx] Liberty is thus surrendered to the time-honored despot and more likely to a new type of despot, unknown in history where the terms “despotism” and “tyranny” do not quite fit. This is characterized by “centralization of governments-the growth of immense tutelary powers which willingly assume the burden of providing for the comfort and well-being of their citizens.” [clxxxi] Democratic men will abandon their freedom to these mighty authorities in exchange for a “soft” despotism, one which “provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry,” and, ultimately, “spare[s] them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living.”[clxxxii]” [clxxxiii] In this new despotism, the “society in which all are equal, independent, an impotent, one agency alone, the state, is specially prepared to accept and to supervise the surrender of freedom.” [clxxxiv]

He posited three variant of despotism which are familiar to us. The first is military despotism as “guardians”[clxxxv] which could emerge as a result of the “relaxation of democratic manners” and the “restless spirit of the army.” Such would be mild, without the “fierce characteristics of a military oligarchy” as “a sort of fusion would take place between the habits of official men and those of the military service.”[clxxxvi] Yet, the restlessness of military increases. The second is when power is vested “in the hands of an irresponsible person or body of persons.”[clxxxvii] This is the worst.[clxxxviii] The third the “combination,” “compromise” and “alternation” between “administrative despotism”[clxxxix] under the “principle of centralization” and a “sole, tutelary, and all powerful form of government”[cxc] and the “popular sovereignty” of the people, where the people have the right to vote, thus, “some of the outward forms of freedom.”[cxci]

“Our contemporaries are constantly excited by two conflicting passions; they want to be led, and they wish to remain free: as they cannot destroy either one or the other of these contrary propensities, they strive to satisfy them both at once.”[cxcii] They “console themselves for being in tutelage by the reflection that they have chosen their own guardians” but “have surrendered it to the power of the nation at large.”[cxciii] This third type comes with three observations. Firstly, this compromise leads to “strange paradoxes”[cxciv] The “representation of people in every centralized country” diminishes “the evil which extreme centralization may produce, but not to get rid of it.”[cxcv] Individuals can intervene in “more important affairs” but “suppressed in the smaller and more private ones.”[cxcvi] Yet the former is less important than the latter.[cxcvii] And it is dangerous to “enslave men in the minor details of life,”[cxcviii] to which “they are led to surrender the exercise of their will.”[cxcix]

“To manage those minor affairs in which good sense is all that is wanted – the people are held to be unequal to the task, but when the government of the country is at stake, the people are invested with immense powers; they are alternately made the playthings of their ruler, and his masters – more than kings, and less than men.”[cc] “It is in vain to summon a people, which has been rendered so dependent on the central power, to choose from time to time the representatives of that power; this rare and brief exercise of their free choice, however important it may be, will not prevent them from gradually losing the faculties of thinking, feeling, and acting for themselves, and thus gradually falling below the level of humanity[cci] … It is, indeed, difficult to conceive how men who have entirely given up the habit of self-government should succeed in making a proper choice of those by whom they are to be governed; and no one will ever believe that a liberal, wise, and energetic government can spring from the suffrages of a subservient people.”[ccii]

Secondly, “After having exhausted all the different modes of election, without finding one to suit their purpose, they are still amazed, and still bent on seeking further; as if the evil they remark did not originate in the constitution of the country far more than in that of the electoral body.”[cciii] Thirdly, “A constitution, which should be republican in its head and ultramonarchical in all its other parts, has ever appeared to me to be a short-lived monster. The vices of rulers and the ineptitude of the people would speedily bring about its ruin; and the nation, weary of its representatives and of itself, would create freer institutions, or soon return to stretch itself at the feet of a single master.”[cciv] We thus left “democratic liberty, or the tyranny of the Caesars.” [ccv] “subservient people” without “the habit of self-government” “they will soon become incapable of exercising the great and only privilege which remains to them.”[ccvi] Tocqueville noted;

“The Americans have combated by free institutions the tendency of equality to keep men asunder, and they have subdued it. The legislators of America did not suppose that a general representation of the whole nation would suffice to ward off a disorder at once so natural to the frame of democratic society, and so fatal: they also thought that it would be well to infuse political life into each portion of the territory, in order to multiply to an infinite extent opportunities of acting in concert for all the members of the community, and to make them constantly feel their mutual dependence on each other. The plan was a wise one.”[ccvii]

This was largely secured by the Northwest Ordinance. The “natural passion for freedom must be supplemented by the political art, an art which Tocqueville finds has been practiced in an exemplary way by America. The American experience suggests for the resolution of the democratic problem certain “democratic expedients, such as local self- government, the separation of church and state, a free press, indirect elections, an independent judiciary, and the encouragement of associations of all descriptions.[ccviii] The most important democratic expedient related to political form are free associations. For Tocqueville, the science of association, which includes local government and as the basis of liberty, is the mother of science in a democracy.[ccix]

Just as Nico Steytler noted that the local government is the “participatory institutions of self-government,”[ccx] Tocqueville thought that only by association can people stand against the government[ccxi] and that voluntary associations are to “supply the individual exertions of the nobles, and the community would be alike protected from anarchy and from oppression.”[ccxii] The “principle of self-interest rightly understood – “the heart of Tocqueville’s resolution of the problem of democracy,” [ccxiii] is but a product of the local self-government; “the locus of the transformation of self-interest into patriotism” … “transform essentially selfish individuals into citizens whose first consideration is the public good.” [ccxiv] (728, 864)

“Tocqueville acknowledges the value of local freedom at the township and community level. Within the confines of this smaller whole, each citizen receives his initial training in the use of freedom. By learning to care for and to cooperate in matters within his own purview, the citizen imbibes the rudiments of public responsibility. The township is the locus of the transformation of self-interest into patriotism, at least into a species of patriotism. According to Tocqueville, free institutions, particularly those at the local level, transform essentially selfish individuals into citizens whose first consideration is the public good. Still, the importance or perhaps the relevance Tocqueville attaches to local self-government may easily be overstated.” [ccxv]

Nevertheless, a democratic regime may achieve viability if a certain enlargement of view does occur; the free institutions Tocqueville recommends are designed to facilitate this. Though, Tocqueville “nowhere gives a simple or a comprehensive formula for the determination of the affairs which properly belong to local as distinct from national authorities,” [ccxvi] Tocqueville may have avoided this to discourage the universalization of the American neo-Aristotelian republican local authorities. Other important expedients related to laws are the separation of church and state, a free press, indirect elections, an independent judiciary. Tocqueville noted that refined manners is derived from choice, habits and education.[ccxvii]

“It must be recognized that Tocqueville does not simply recommend the adoption of each and every American practice. Although he admires the federal system, for example, he argues that such a complicated mechanism is wholly unsuited to the temperament and realities of European political life. More than anything else, America provides the principles, such as the principle of self-interest rightly understood, upon which a respectable democratic order might be constructed.” [ccxviii] He was concerned about “the community prepared to make great sacrifices with little difficulty?”[ccxix]

According to Tocqueville, United States is the most perfect federal constitution in the world,[ccxx] but when ill adapted by a people without the republican manners of enlightened self-interest and of self-government becomes a disaster.[ccxxi] He cited the examples of Mexico who adopted the American laws without the manners,[ccxxii] Mexico adopted the constitution of the United States, but turned into standing armies between them.[ccxxiii] These problems are the contemporary and great challenges in Africa apathy for public business and need to combat individualism.[ccxxiv]

Tocqueville’s Cultivation of the Arts

Another important democratic expedient, amongst other, is the Arts. Tocqueville noted that American like to “cultivate the arts which serve to render life easy, in preference to those whose object is to adorn it. They will habitually prefer the useful to the beautiful, and they will require that the beautiful should be useful.” (560) And he also warned that “in the useful arts” as well as “fine arts” the productions “of artists are more numerous, but the merit of each production is diminished.”[ccxxv]

However, he also noted that “those who direct our affairs” are “to teach democracy.”[ccxxvi] And such would obviously include all aspects including architecture and urbanism. Tocqueville would particularly state this that;

“men require much intelligence, knowledge, and art to organize and to maintain secondary powers under similar circumstances, and to create amidst the independence and individual weakness of the citizens such free associations as may be in a condition to struggle against tyranny without destroying public order.”[ccxxvii] (Italics is mine)

Involvement in urban modification in connection to common sense is another way to teach the necessary manners of enlightened self-interest. Tocqueville noted, “if it be proposed to make a road cross the end of his estate, he will see at a glance that there is a connection between this small public affair and his greatest private affairs; and he will discover, without its being shown to him, the close tie which unites private to general interest.”[ccxxviii] Also, he noted “If a stoppage occurs in a thoroughfare, and the circulation of the public is hindered, the neighbors immediately constitute a deliberative body; and this extemporaneous assembly gives rise to an executive power which remedies the inconvenience before anybody has thought of recurring to an authority superior to that of the persons immediately concerned.”[ccxxix]

Such modification of architectonic means, primary activities with trading and dwelling (the architectonic economic sense) according to Tocqueville would lead to the “Urbanity of manners”[ccxxx] through the enlightened self-interest.

Recollection

The concern for the small self-governing community as the school of and for republican virtue was one of the major themes pushed by the Anti-Federalists against the Federalists during the founding of the United States. Carol M. Rose recollected that Anti-Federalists held “that character must be nourished by institutions” and that “initiative and optimism are character traits that the Federalist Constitution needs too, not only for political life but for commerce as well.” [ccxxxi]

Aside from the Bill of Right, another interesting compromise between the anti-Federalists and the Federalists to me, which is de-emphasized in history, appear to be the Northwest Ordinances of 1787. Whilst the new 1789 Constitution, based on the de-ontological and modern constitutionalism, was introduced to secure the second polycentric element – “existence of a single system of rules” that the earlier Article of Confederation lacked, the local government principles based on the ontological, civilizational and ancient constitutionalism were preserved and secured within a federal structure through the Northwest Ordinances of 1787, leading to – Janus Effects -a binary complementarity, by means of which the ancient constitutionalism could shore up the lifeless modern constitutionalism with virtue and character.

The Federalist 1789 Constitution is like a hardware whilst the 1787 Northwest Ordinance is like the software.

And this shoring up manifests on three levels; civic form; political form; and architectural and urban form, in a two-step transformation. Succinctly, the progression is a two-step transformation from the city of classic natural right and moral virtues, that is, the politiea (“form of the city” [ccxxxii] or regime[ccxxxiii]or simply “a way of life” [ccxxxiv]) to the amendable laws of that politiea and from that to the equally amendable physical city created to serve the politiea (classical architecture and urban forms[ccxxxv]). This two-step transformation would eventually lead to an assemblage of the civic form of the city, political form of the city and the urban form of the city, towards “the chief purpose of the city” which is “the noble life” and “the virtue of its members and hence liberal education.”[ccxxxvi] These provide the basis of nourish character.

Only in this shoring the modern constitutionalism up with the ancient constitutionalism could we be reminded, according to Strauss, that liberal democracy ‘‘is meant to be an aristocracy which has broadened into a universal aristocracy’’; that ‘‘liberal education is the ladder by which we try to ascend from mass democracy to democracy as originally meant.’’”[ccxxxvii] And through that we can shore up democracy.

This Janus Effects is what was codified by Tocqueville as the new science that emphasized enlightened self-interests, local self- government, and other major political expedients including the Arts. And this was helpful in the development of polycentricity by Vincent and Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School.

Aside from shoring up the modern constitutionalism with character and virtue, the Janus Effect is vital to the creation of a multi-party system, as well as a mechanism of “unsolved and even insoluble problems” to keeps the nation going as long as the generic Manichean duality of two heads or what I call, the Janus Effects, is preserved. And through that “the regime in troubled motion” would find means to negotiate survival during “periods of great tension or struggle over the meaning of the regime,”[ccxxxviii] as long as the ancient constitutionalism is preserved.

Thomas Pangle noted that an encounter with Straussian-Tocquevillian science could make us discover the “important thing” is “above all our way back to the truly most urgent and serious issues that have been buried from our sight.[ccxxxix] One of these things buried from our sight is the Janus Effects effected by the Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance. Pangle also states “‘‘We cannot exert our understanding without from time to time understanding something of importance; and this act of understanding may be accompanied by the awareness of our understanding,’’ by noesis noeseos—‘‘so noble an experience that Aristotle could ascribe it to his God.’’“[ccxl]

What is said about Strauss could be said as the massive foreground of Westfall’s lifework, who wrote extensively on Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance. Whilst Strauss was concerned about the neo-Aristotelean political science that is also Tocquevillean-Straussian political science,[ccxli] Westfall, a student of Strauss, is concerned about the classical architectural principles (Vitruvius and Alberti) that is affected by the Tocquivellean-Straussian political science as an echo of “neo-Aristotelian political science.” Thus, both Strauss’ resuscitation of Aristotelean political science and Westfall’s resuscitation of classical architectural principles are not only coeval with Tocquevillian political science, but are also tied together by it.