The Nigerian Dream

July 16, 2019

Janus Effects and Nourishing Character with Institutions

April 14, 2024By Olusegun R. Babalola

“… a constitution, which leads away from a highly centralized state towards a limited state, must be the bargain of self-governing social forces covenanting with each other. Such a new constitutional order based on democracy can only be realised through the strengthening and building of the polycentric nature of society, where self-governance in key areas of social life may eventually lead to transforming the political system into one expressing constitutionalism and, where needed, federalism.” [292]

- Nico Steytler, Domesticating The Leviathan: Constitutionalism and Federalism in Africa in African Journal of International and Comparative Law 24.2 (2016): 272–292, Edinburgh University Press.

The post-independence reality of “two publics;” amoral, colonial and formal state[i] that subjugates the moral, primordial and informal governance institutions,[ii] well captured by several African scholars such as Peter Ekeh, Louis Munoz and Nico Steytler amongst others, is the primal lever of coloniality of being, of knowledge, and especially of power in Africa. For political stability and economic development in a vibrant liberal democracy with a domesticated Leviathan, the two publics must be de-colonized – collapsed into a single, moral, decentralized and polycentric public with the existence of several centers for decision making; of a single system of rules; and of a spontaneous social order as “the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life.” This de-colonializatiom of local authorities through polycentricity is to further lead to “transforming the political system into one expressing constitutionalism and, where needed, federalism.”[iii]

Whilst discussing the successes and failures of the third wave of constitution-making and liberal democracy in Africa after the Cold-War, the South African Nico Steytler draws our attention in his 2016 Domesticating the Leviathan: Constitutionalism and Federalism in Africa,[iv] to the African crisis of constitutionalism and federalism.

According to Steytler the post-1989 constitutions”[v] in Africa after the Cold War “by and large reflected a new and different constitutional paradigm of horizontally and vertically divided power.”[vi] However, “the new constitutions adopted did not, however, fundamentally change the exercise of sovereignty and thus by and large failed to domesticate the Leviathan.”[vii] Gap remains “between the constitutions on paper and constitutionalism, the practice of limited government.”[viii] Steytler presented a sharp contradistinction between how the West [Europe and United States] domesticated the Hobbes’ Leviathan and how we (Africans) have been unable to. Constitutions are there, according to him but “constitutionalism is yet to be consolidated.”[ix]

Steytler also sheds eminent lights on the African crisis of constitutionalism and federalism by clearly identifying four continuities and discontinuities of the colonial Leviathan in the present African post-independent Leviathan. First is Hobbes’ over-centralization which he calls the continuity of the colonial Hobbes’ Leviathan, what Vincent Ostrom and his co-authors called gargantua. The second is what Peter Ekeh had identified as the “two publics” of the colonial/post-colonial; amoral “civic” public: and the more responsive indigenous and moral “primordial” public. This is coupled with the program of “de-ethnicisation” of the moral “primordial” public for the sake of an artificial nation building.

The third is the demand for obedience even without accountability and equity or modern natural right. As a result, African democracies are “monocentric system (authoritarian or not)”; and may appropriately be defined as the monocentric African “illiberal democracies or semi-democracies,” [using Steytler’s words[x]] spurning apathy rather that patriotism and leaving the state without citizenship. The fourth, as is obvious to us all, is the absence of peace, security and hence, political stability for development, with the fatal realities of cyclic alternation of anarchy and despotism what Alexis de Tocqueville called “general apathy.”

Steytler hints us about Ostrom twin advise. The first advice is “that Africans could learn how their former colonial masters” domesticated “the Leviathan in old and modern European history first by securing the recognition of the autonomy of the organs of civil society, and second by dispersing power at the centre through the separation of powers.[xi]” The second Ostrom’s advice challenged Africans “to discover in their own history, values, experience and traditions, a path that leads away from the highly centralized state and towards self-governance.’[xii]99” [289-290][xiii]

It is in understanding how the West domesticated the Leviathan, that we would discover that the “two publics” above stated is the lever of coloniality. Toyin Falola sheds lights on this “response, reaction, and resistance to hegemonic epistemic traditions of the European world, which began and ended before the conferment of independence on the colonized peoples, cannot necessarily explain the situation of colonization, which has continued to manifest itself even after the physical termination of the colonial imperialists from the power bases of different African countries.”[xiv] Falola continues;

“liberation from the European stranglehold did not translate to emancipation from its mental shackles. As such, decolonization did not translate to the freedom of the colonized people. Instead, it set the stage for the continuation of servitude under the imperial systems. For instance, scholars have contended that the so-called independence given to many African countries was one located, if not confined, in the hands and control of a tiny elite. On their part, many members of this tiny elite have been projected to be mirror images of Western and Eurocentric traditions and values, from which their essence and agenda draw inspiration. In essence, the task of questioning specific inherited legacies was shirked by this elite, who were the beneficiaries of the structures and powers that independence created. Consequently, political, economic, social, epistemic, and ontological relics systematically institutionalized by the European colonialists in their heydays were left unquestioned and, by necessary implications, untouched or modified.” [xv]

Along this line, Steytler also discussed how African liberal democracy could domesticate the inherited colonial Leviathan through the cultivation of polycentric society towards genuine liberal constitution and constitutionalism, and also federalism “where needed.”[xvi]

Case for Self-Governing Associations of a Polycentric Society

Steytler noted three alternatives to domesticating the Leviathan; “necessary capacity-building an illegitimate constitution;” “legitimating constitution-making and its content;” and long term “incremental societal change” on how the gap between the constitution on paper and its effective implementation can be closed,”[xvii] The first alternative, “the good-governance model favoured by the international community” is on capacity-building, concerned with pulling the “illegitimate constitution” by “its own bootstraps”[xviii] or “redemptive constitutional practice” through “effective implementation” to bestow legitimacy of the illegitimate constitution.

The second alternative is based on the observation of the “lack of legitimacy by birth and pedigree,”[xix] and “finds the fault in the constitution itself,”[xx] its “process and values”.[xxi] This entails fixing “the legitimacy of the constitution” through the replacement of “foreign-based orientation” with the “values, beliefs and norms of indigenous African cultures’[xxii]. A new constitution should “emerge ‘only from widespread popular debates, dialogues, and consultations’ that build a state on a basis of popular sovereignty[xxiii]” and to “enable ordinary people to assert ownership over the state and other political institutions’.[xxiv]”

The third alternative points to the “larger problem – that of the nature of the social compact as articulated in the constitution,”[xxv] which reveals “the constitutions are yet to be a social compact of competing social forces that have the interest and capacity to ensure compliance,”[xxvi] and also, the “problems with constitutional design itself.”[xxvii] “Constitutionalism, the practice of constitutional democracy” according to him “is the product of three key factors, politics (state), the economy and society.”[xxviii] This focuses on “societal changes” – on “how change could be effected” on the “establishment of constitutionalism” through “values and processes” that are directed at how the transformed society could domesticate the Leviathan, and as such through “a slow and incremental process.”[xxix]

Steytler would rule out the first option, and go for the third polycentric option with a selective adoption of some elements in the second option. He continued “constitutions are not the grand bargain of selfgoverning associations of a polycentric society, covenanting among themselves how to domesticate the Leviathan, the citizens or interest groups are unlikely to come forward ‘to pay the price of civil disobedience’ in challenging the constitutionality of governmental action[xxx] and finding a receptive and independent judiciary.[xxxi] [italics is mine] Steytler concluded;

“… a constitution, which leads away from a highly centralized state towards a limited state, must be the bargain of self-governing social forces covenanting with each other. Such a new constitutional order based on democracy can only be realised through the strengthening and building of the polycentric nature of society, where self-governance in key areas of social life may eventually lead to transforming the political system into one expressing constitutionalism and, where needed, federalism.”[xxxii]

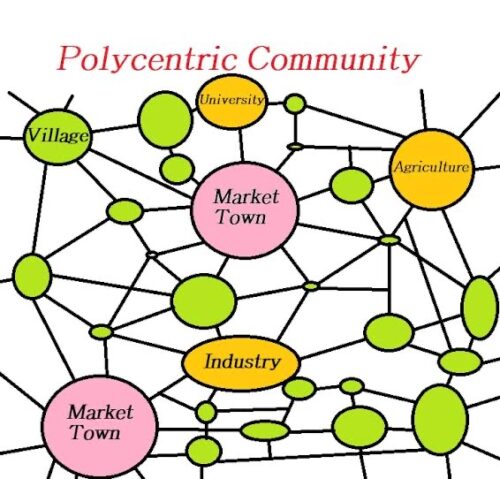

The questions are; what are self-governing associations of a polycentric society? How can such society employ the three key factors, politics (state), the economy and society towards a “social compact” that would make way for constitutionalism and, where needed, federalism”? And most of all – what is polycentricism? We cannot understand how polycentricity can be useful before we have comprehensively understood it.

What is Polycentricity?

Polycentricity was first envisaged by Michael Polanyi, in his 1951 book The Logic of Liberty,[xxxiii] where he was concerned about “preserving the freedom of expression and the rule of law,” [xxxiv] against the Socialist “monocentric” system [xxxv] which is a moral system that diminishes freedom and disguises as a scientific system. Polanyi argued that the success of science, art, religion, or the law are as a result of “polycentric organization” of “multitude of opinions” and “progress” as “the outcome of a trial-and-error evolutionary process of many agents interacting freely.” According to him, the “hidden system of things” would be jointly discovered if the steps taken are guided by competence and an “invisible hand.” Polycentric studies would spread to law studies (Lon Fuller, Chayes A. and Donald Horowitz); urban networks studies (Simin Davoudi, Charles Hague and Kesten Kirk); and governance studies (Vincent and Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School).

Inspired by the American constitution, constitutionalism and Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, “Vincent Ostrom and his associates” too, confronted the advocates of “monocentric” or centralized system during the 1960s debate on “public administration reform in American metropolitan areas.” Vincent Ostrom and his associates held that designing the American constitution could be viewed as an experiment in polycentricity while federalism could be seen as one way to capture the meaning and to operationalize one aspect of this type of order. And, in light of that insight, polycentricity seems to be a necessary condition for achieving “political objectives” such as liberty and justice.” [xxxvi] “The dispersion of decision-making capabilities associated to polycentricity,” according to Ostrom, “allows for substantial discretion or freedom to individuals and for effective and regular constraint upon the actions of governmental officials” and as such is an essential characteristic of democratic societies.”[xxxvii]

Ostrom sought to defend the traditional “multiplicity of federal and state governmental agencies, counties, cities and special districts that govern within a metropolitan region.” On this “monocentric” system, with “the monopoly over the legitimate exercise of coercive capabilities,” Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren penned in 1961;

“This view assumes that the multiplicity of political units in a metropolitan area is essentially a pathological phenomenon. The diagnosis asserts that there are too many governments and not enough government. The symptoms are described as duplication of functions” and “overlapping jurisdictions.” Autonomous units of government, acting in their own behalf, are considered incapable of solving the diverse problems of the wider metropolitan community. The political topography of the metropolis is called a “crazy-quilt pattern” and its organization is said to be an “organized chaos.” The prescription is re-organization into larger units-to provide “a general metropolitan framework” for gathering up the various functions of government. A political system with a single dominant center for making decisions is viewed as the ideal model for the organization of metropolitan government. “Gargantua” is one name for it.” [xxxviii]

The three authors conceded that “Gargantua unquestionably provides an appropriate scale of organization for many huge public services. The provision of harbor and airport facilities, mass transit, sanitary facilities and imported water supplies may be most appropriately organized in gargantua. By definition, gargantuan should be best able to deal with metropolitan-wide problems at the metropolitan level.” [xxxix] However, they also held that “some consideration should be given to the problem of organizing for different types of public services in gargantuan.” [xl] They all argued;

“… gargantuan with its single dominant center of decision-making, is apt to become a victim of the complexity of its own hierarchical or bureaucratic structure. Its complex channels of communication may make its administration unresponsive to many of the more localized public interests in the community. The costs of maintaining control in gargantua’s public service may be so great that its production of public goods becomes grossly inefficient. Gargantua, as a result, may become insensitive and clumsy in meeting the demands of local citizens for the public goods required in their daily life. Two to three years may be required to secure street or sidewalk improvements, for example, even where local residents bear the cost of the improvement. Modifications in traffic control at a local intersection may take an unconscionable amount of time. Some decision-makers will be more successful in pursuing their interest than others. The lack of effective organization for these others may result in policies with highly predictable biases. Bureaucratic unresponsiveness in gargantuan may produce frustration and cynicism on the part of the local citizen who finds no point of access for remedying local problems of a public character. Municipal reform may become simply a matter of “throwing the rascals out.” [xli]

They noted that just as any “island of polycentric order entails and presses for polycentricism in other areas, creating a tension toward change in its direction,” [xlii] the same goes for monocentric islands leading to “an unstable coexistence” [xliii] between monocentrism and polycentricity. It is for this reason that the primordial public with the diverse pro-polycentric proclivities are rigidly kept out of Nigerian constitutional formation, due to their propensity for spontaneity.

The three authors affirmed that “various scales of organization may be appropriate for different public service in a metropolitan area”[xliv] and that “The traditional pattern of government in a metropolitan area with its multiplicity of political jurisdictions may more appropriately be conceived as a “polycentric political system.” [xlv] And that unlike the polycentric order, “The citizen may not have access to sufficient information to render an informed judgment at the polls. Lack of effective communication in the large public organization may indeed lead to the eclipse of the public and to the blight of the community.” [xlvi]

Vincent Ostrom, C. M. Tiebout, and R. Warren, in 1961, defined the term polycentric;

“Polycentric” connotes many centers of decision-making which are formally independent of each other. Whether they actually function independently, or instead constitute an interdependent system of relations, is an empirical question in particular cases. To the extent that they take each other into account in competitive relationships, enter into various contractual and cooperative undertakings or have recourse to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts, the various political jurisdictions in a metropolitan area may function in a coherent manner with consistent and predictable patterns of interacting behavior. To the extent that this is so, they may be said to function as a “system.”[xlvii]

Three Elements of Polycentricity

The “concept of polycentricity,” according to Paul D. Aligica and Vlad Tarko[xlviii] in their article Polycentricity: From Polanyi to Ostrom, and Beyond, is “a structural feature of social systems of many decision centers having limited and autonomous prerogatives and operating under an overarching set of rules.”[xlix] There are 3 basic element of polycentricity (emphasized by the Bloomington school approach). And these are

(1) The existence of many centers for decision making,

(2) the existence of a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced), and

(3) the existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life.”[l]

On the “existence of many centers for decision making,” polycentricity “emerges as a nonhierarchical, institutional, and cultural framework that makes possible the coexistence of multiple centers of decision making with different objectives and values, and that sets up the stage for an evolutionary competition between the complementary ideas and methods of those different decision centers. The multiple centers of decision making may act either all on the same territory or may be territorially delimitated from each other in a mutually agreed fashion.”[li] These centers would have “many centers of decision making” and “ordered relationships that persist in time.” [lii]

The “existence of a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced),” is important because “the existence of multiple centers of decision making can degenerate into social chaos” without rules and such “polycentric order” could break down to “monocentric system (authoritarian or not), or to chaotic violent anarchy.” “In a polycentric political system, no one has an ultimate monopoly over the legitimate use of force and the “rulers” are constrained and limited under a “rule of law.”” [liii] Thus, organizations that are analogous to “polycentric order” without “an encompassing system of rules” are not polycentric at all. Thus, in “defining a polycentric system, the notion of “rule” is as important as the notions of “legitimacy,” “power,” or multiplicity of “decision centers” are.” [liv]

According to Aligica and Tarko territorial jurisdiction, rules designed by outsiders would make rules ”illegitimate”,[lv] thus “agents directly involved in rule design” can “be considered the essential attribute of a democratic system.”[lvi] Most of all, the existence of a single system of rules would accommodate “many legitimate rules enforcers, single system of rules,” and “ centers of power at different organizational levels.” [lvii]

The “existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life” entails that a community, within the connecting federating state or region could spontaneously create new local governments. “Spontaneity means that “patterns of organization within a polycentric system will be self-generating or self-organizing” in the sense that “individuals acting at all levels will have the incentives to create or institute appropriate patterns of ordered relationships.” “Thus, polycentric systems are more likely than monocentric systems to provide incentives leading to self-organized, self-corrective institutional change.”[lviii]

Three things are important for the ever-evolving “spontaneous development of the system” and these are “the freedom of entry and exit in a particular system;” incentives to “enforce general rules of conduct;” and capacity for “reformulation and revision of the basic rules” with procedural “rules on changing rules” and cognitive rules with “an understanding of the relationship between particular rules and the consequences of those rules under given conditions.” [lix] [lx]

Thus, knowledge and learning are vital for this spontaneity. Thus, “discussion on polycentricity is not just a discussion about multiple decision-making centers and monopolies of power, but also a discussion about rules, constitutions, fundamental political values, and cultural adaptability in maintaining them.”[lxi] According to Aligica and Tarko; majority rule, merit-based entry, constrained exit and private information do “make the polycentric system more vulnerable.”[lxii]

Furthermore, Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren noted that these three basic principles of polycentricity are evident in the American local government, and the American constitutional rules, government, civil society and the private sector. [lxiii] The three authors noted

“The conditions attending the organization of local governments in the United States usually require that these criteria be controlled by the decisions of the citizenry in the local community, i.e., surbordinated to the considerations of self-determination. The patterns of local self-determination manifest in incorporation proceedings usually require a petition of local citizens to institute incorporation proceedings and an affirmative vote of the local electorate to approve. Commitments to local consent and local control may also involve substantial home rule in determining which interests of the community its local officials will attend to and how these officials will be organized and held responsible for their discharge of public functions.” [lxiv]

Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren further noted

“Local Self-government of municipal affairs assumes that public goods can be successfully internalized. The purely “municipal” affairs of a local jurisdiction, presumably, do not create problems for other political communities. Where internalization is not possible and where control consequently, cannot be maintained, the local unit of government becomes another “interest” group in quest of public goods or potential public goods that spill over upon others beyond its borders. The choice of local public services implicit in any system of self-government presumes that substantial variety will exist in patterns of public organization and in the public goods provided among the different local communities in a metropolis. Patterns of local autonomy and home rule constitute substantial commitments to a polycentric system.” [lxv]

The application of polycentricity led to two things. The first is a polycentric “social philosophy of social order.” The second is the empirical application of the polycentric paradigm. The case for the gargantuan was contradicted by “Elinor and Vincent Ostrom and their team” [lxvi] through “a solid empirical research agenda” [lxvii] that was arrived at not through speculations but “data” collected “out in the field.” [lxviii] The empirical application of the polycentric paradigm led to the development of an applied institutional analysis and development (IAD framework) and the social–ecological system (SES) framework by the Ostroms’ Bloomington school. Elinor Ostrom, 2009 Nobel Prize in economics, wrote that scholars use IAD “to analyze a diversity of puzzles”[lxix] is applied to a “variety of important policy questions”[lxx] and the “foundation for research in policy analysis”[lxxi] and that SES framework is a “more complex framework for the analysis” that IAD framework.

How Coloniality Frustrates the Emergence of a Polycentric Order

Yash Ghai suggested “in the West it was society that shaped the state, while in colonial and post-colonial Africa, the state has so far shaped society.”[lxxii] The post-independence continuities of the colonial Leviathan have all combined to frustrate the emergence of a strong society across ethnic lines which could modify the state as the Western societies does. Steytler reveals the absence of a strong society made up of “self-governing associations”[lxxiii] and “social forces to sustain the federal compact”,[lxxiv] through which it “cannot bring itself to life”. [lxxv]

The question is – what is frustrating the capacity of the society to employ the three key factors, politics (state), the economy and society towards a “social compact” that would make way for constitutionalism and, where needed, federalism”? In short, what has made this social compact un-achievable?

Coloniality and Political Polycentricism

Steytler would identify two issues here. One is the de-concentration of the local government and the second is the tragical constitutionally exclusion of the indigenous polities. This is partly, “as a result the problems with constitutional design itself,”[lxxvi]

The local government as the “participatory institutions of self-government,”[lxxvii] which according to Tocqueville is one of the major … in democracy remain the extensions of central governments.[lxxviii] Steytler noted that “Even local governments, supposedly participatory institutions of self-government, ‘in practice . . . are more of an extension of central government to the local level where bureaucracy and machine politics prevail’; in other words, ‘it is a centralized system at the grass roots’.[lxxix]” After the 1989 paradigm shift, just as the fact that federal “arrangements have not been reflected in a federal polity and culture,”[lxxx] The “decentralisation through local government” which is evident in many of the liberal democratic constitutions that were adopted since 1989 “remains at best a form of deconcentration.”[lxxxi]

2007 African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance [African Charter] that came into force in 2012 affirms in the Preamble that the “values and norms of constitutional democracy” were not “Western constructs, but as ‘universal values and principles.’”[lxxxii] The Charter also affirms the importance of rule of law and the horizontal division of powers;”[lxxxiii] and stressed that “the democratic nature of local government.” Yet the 2007 African Charter “does not entail constitutionalising local self-government, but leaves it to the national legislatures to decentralise powers.”[lxxxiv]

Secondly, the “postcolonial constitutions had remained opposed to traditional authority structures.” [280] Though, the 2007 African Charter emphasizes the importance of the universal democratic values and principles, and recognizes “traditional authorities,” it is according to Steytler “inevitably cautious over the role of traditional authorities.” Article 35 states; ‘Given the enduring and vital role of traditional authorities, particularly in rural communities, the State Parties shall strive to find appropriate ways and means to increase their integration and effectiveness within the larger democratic society.’[lxxxv] The 2007 African Charter speaks of “the historical and cultural conditions in Africa” in the Preamble and also in Article 27, section 9 of African Charter emphasizes the importance of “Harnessing the democratic values of the traditional institutions.” Steytler concluded that the “obligation imposed is the aspirational one of ‘striving towards a vague goal of finding ‘appropriate ways and means’ towards integration, not within a system of governance, but within ‘larger democratic society’.”[lxxxvi]

The colonial Leviathan “brought traditional authorities into its service,”[lxxxvii] and the post-independence Leviathan has just continued it. Steytler wrote “On the one side is the formal state (acting in its own interest or for an exclusive group) and on the other are informal governance institutions (social institutions and processes working for people’s daily survival).”[lxxxviii]

This pathological phenomenon is described by Louis Munoz as “fatal dualism.”[lxxxix] As Peter Ekeh taught, we have “the existence of two publics instead of one public, as in the West;” the moral “primordial public” and the colonial and amoral “civic public,” whilst both are kept separate the former is imposed on the latter. For absolute rule, the two publics were created, and the primordial public was transformed into colonial servants. Peter Eketh penned,

“there are two public realms in post colonial Africa, with different types of moral linkages to the private realm. At one level is the public realm at which the primodial groupings, ties and sentiments, influence and determine the individual’s public behaviour. This is the primordial public because it is closely identified with primordial grouping, sentiment and activities which nevertheless impinge on the public interest. On the other hand, there is a public realm which is historically associated with the colonial administration and which has become identified with popular politics in post-colonial Africa. It is based on civil structures: the military, the civil service, the police, etc. Its chief characteristic is that it has no moral linkages with the private realm. I shall call this the civic public. The civic public in Africa is amoral and lacks the generalized moral imperatives operative in the private realm and in the primordial public.”[xc]

This is not something you would find in successful states where there is political stability for economic development. And this fatal dualism between the two publics is the genesis of “Many of Africa’s political problems.”[xci]

To understand this, one could take a look at Olusegun Obasanjo’s biography, My Watch (Vol 1, p65), and see the map of Abeokuta with spontaneous moral “primordial public” in brown and beside it is the well-planned square donut of the powerful amoral “civic public,” the Government Reserved Area (GRA), formerly called, the European Residential Areas [ERAs]. [xcii] The pan-tribalists or “ethnic entrepreneurs” (to use Obasanio’s terms) eventually became the amoral colonial agents who replaced the colonial powers in the decision-making GRAs, with control of the modern and amoral civic public over the moral primordial public.

Despotism

Ostrom and the Bloomington school were significantly influenced by Tocqueville who stated that the passion for equality “would cause citizens to place great powers in the hands of a government charged with eradicating inequalities” (see Tocqueville[xciii]) and as a result as Russell L. Hanson put it “liberty would eventually succumb to a kind of democratic despotism, unless the passion for equality was balanced by other considerations or values.” [xciv]

The cause is “That social condition which is the moving principle of democratic regimes is the condition of equality. For Tocqueville, this is the “fundamental fact from which all others seem to be derived.”[xcv]””[xcvi] There is a difference between equality of conditions which has taken roots in America and in-equality of conditions[xcvii] as “the social state of the old regime, either of France or of feudal Europe generally.”[xcviii] To the “old regime” “Tocqueville ascribes to an aristocratic state of society: a certain elevation of mind and scorn of worldly advantages, strong convictions and honorable devotedness, refined habits and embellished manners, the cultivation of the arts and of theoretical sciences, a love of poetry, beauty, and glory, the capacity to carry on great enterprises of enduring worth.” [xcix] “The characteristic feature of democratic society is its atomism.” [c]

Men confront each other as equals, each independent, each impotent.” [ci] “According to Tocqueville, the key to the atomistic quality of democratic ages lies in the diffusion of “individualism,”.” [cii] “Wholly absorbed in the contemplation of this universe, the individual loses sight of that greater universe, society at large.” [ciii]“ When individualism is linked with equality of conditions, an insatiable thirst develops for the material comforts of this world. In a society shorn of the traditional restraints and obligations—to country, to lords, to church—“where the materially comfortable nobility and ruling class made way for the cultivation of the higher faculties ”men strive eagerly to gratify their immediately felt and immediately intelligible desires to improve their conditions of life.”[civ]

“The fundamental paradox of democracy, as Tocqueville understands it, is that equality of conditions is compatible with tyranny as well as with freedom. A species of equality, at least, can coexist with the greatest inequality.”[cv] “The passion of men of democratic communities for equality is ardent, insatiable, incessant, invincible; they call for equality in freedom, and if they cannot obtain that, they still call for equality in slavery.” [cvi] As a result of equality, “it is easier to establish an absolute and despotic government amongst a people in which the conditions of society are equal, than amongst any other” and would oppress them and “strip each of them of several of the highest qualities of humanity.”[cvii]

Tocqueville was particularly critical of despotism. Unfortunately, the “wisest” are often alarmed by the anarchy rather than the despotism.[cviii] Equality thus prepares man to surrender his freedom to safeguard equality itself.” [cix] Liberty is thus surrendered to the time-honored despot and more likely to a new type of despot, unknown in history where the terms “despotism” and “tyranny” do not quite fit. This is characterized by “centralization of governments-the growth of immense tutelary powers which willingly assume the burden of providing for the comfort and well-being of their citizens.” [cx] Democratic men will abandon their freedom to these mighty authorities in exchange for a “soft” despotism, one which “provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry,” and, ultimately, “spare[s] them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living.”[cxi]” [cxii] In this new despotism, the “society in which all are equal, independent, an impotent, one agency alone, the state, is specially prepared to accept and to supervise the surrender of freedom.” [cxiii]

Tocqueville posited three variant of despotism which are familiar to us. The first is military despotism as “guardians”[cxiv] which could emerge as a result of the “relaxation of democratic manners” and the “restless spirit of the army.” Such would be mild, without the “fierce characteristics of a military oligarchy” as “a sort of fusion would take place between the habits of official men and those of the military service.”[cxv] Yet, the restlessness of military increases. The second is when power is vested “in the hands of an irresponsible person or body of persons.”[cxvi] This is the worst.[cxvii] The third the “combination,” “compromise” and “alternation” between “administrative despotism”[cxviii] under the “principle of centralization” and a “sole, tutelary, and all powerful form of government”[cxix] and the “popular sovereignty” of the people, where the people have the right to vote, thus, “some of the outward forms of freedom.”[cxx]

“Our contemporaries are constantly excited by two conflicting passions; they want to be led, and they wish to remain free: as they cannot destroy either one or the other of these contrary propensities, they strive to satisfy them both at once.”[cxxi] They “console themselves for being in tutelage by the reflection that they have chosen their own guardians” but “have surrendered it to the power of the nation at large.”[cxxii] This third type comes with three observations. Firstly, this compromise leads to “strange paradoxes”[cxxiii] The “representation of people in every centralized country” diminishes “the evil which extreme centralization may produce, but not to get rid of it.”[cxxiv] Individuals can intervene in “more important affairs” but “suppressed in the smaller and more private ones.”[cxxv] Yet the former is less important than the latter.[cxxvi] And it is dangerous to “enslave men in the minor details of life,”[cxxvii] to which “they are led to surrender the exercise of their will.”[cxxviii]

According to Tocqueville, “To manage those minor affairs in which good sense is all that is wanted – the people are held to be unequal to the task, but when the government of the country is at stake, the people are invested with immense powers; they are alternately made the playthings of their ruler, and his masters – more than kings, and less than men.”[cxxix] It is in vain “to summon a people, which has been rendered so dependent on the central power, to choose from time to time the representatives of that power; this rare and brief exercise of their free choice, however important it may be, will not prevent them from gradually losing the faculties of thinking, feeling, and acting for themselves, and thus gradually falling below the level of humanity.[cxxx] It is, “indeed, difficult to conceive how men who have entirely given up the habit of self-government should succeed in making a proper choice of those by whom they are to be governed; and no one will ever believe that a liberal, wise, and energetic government can spring from the suffrages of a subservient people.”[cxxxi]

Secondly, “After having exhausted all the different modes of election, without finding one to suit their purpose, they are still amazed, and still bent on seeking further; as if the evil they remark did not originate in the constitution of the country far more than in that of the electoral body.”[cxxxii] Thirdly, “A constitution, which should be republican in its head and ultramonarchical in all its other parts, has ever appeared to me to be a short-lived monster. The vices of rulers and the ineptitude of the people would speedily bring about its ruin; and the nation, weary of its representatives and of itself, would create freer institutions, or soon return to stretch itself at the feet of a single master.”[cxxxiii] We thus left “democratic liberty, or the tyranny of the Caesars.”[cxxxiv] and “subservient people” without “the habit of self-government” “they will soon become incapable of exercising the great and only privilege which remains to them.”[cxxxv]

The Nigerian, and in deed the African in-ability of closing the gap between the constitution on paper and its effective implementation is not un-connected to this culture of despotism. It is the fundamental testimonial of the African Leviathan. As a result, African states are “a kind of democratic despotism” or what Steytler called “illiberal democracies” [cxxxvi] and what Pierre Englebert and Denis M. Tull “semi-democracies” where “authoritarian practices and violation of human rights remain commonplace,[cxxxvii]”

Polycentric Analysis

The two-publics reveals “large number of overlapping and interconnected networks of obligations”[cxxxviii] and “existence of many centers for decision making” with the absence of “a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced),” because the amoral and informal primordial public is excluded. In the deconcentrated local government, the rules are drafted by the monocentric and amoral civic public only and there is no “alignment between rules and incentives” for the primordial public. Our local governments are fixed by the State. In Nigeria there were 307 local governments in 1979, and now 774 local governments in 1999 Constitution. And the Constitution provides a uniform rule of administration which is seldom followed in practice, with “the lack of democratic local councils as provided for in the 1999 constitution.” [cxxxix] The hiatus is the absence of “a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life” within an equally absent “overarching system of rules.” As a result, all the connected three indicators like “in terms of whether there exists free exit, in terms of whether the relevant information for decision making is public (available to all decision centers equally) or secret, and finally, in terms of the nature of entry in the polycentric system—free, meritocratic, or spontaneous” [cxl] are all absent.

This is so regardless of the existence of a single system of rules; overarching system of rules; institutional or cultural spontaneity of the disparate “traditional and informal governance structures,” that is, the “social institutions and processes working for people’s daily survival”[cxli] and which are more likely to avoid rigidity. There is no “collective choice,” so we cannot know if “collective choice aggregating mechanism.” There is no exit, no initiative nor optimism. Only gloom.

Coloniality of Power

This modern and lees than human caste system is the coloniality of power, established by the colonial administration as “European constructions” to “dominate”[cxlii] and is continued by Africans themselves. This is precisely what Karen Tucker called “an explicit political order”[cxliii] or what Walter D Mignolo calls “the colonial matrix of power”[cxliv] towards a blind Western capitalist exploitation, expansion and oppression – “the control of economy; control of authority, control of gender and sexuality; and control of subjectivity and knowledge.”[cxlv] It was established as Anibal Quijano argued based on racial hierarchy of superior Europeans and inferior Africans,[cxlvi] but nevertheless continues with the colonial African replacement.

The” two publics” is the major fulcrum of coloniality, what Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni calls “the oppressive character of the racially-organized, hegemonic, patriarchal and capitalist world order alongside Euro-American epistemological fundamentalism that denies the existence of knowledge from non-Western parts of the world.”[cxlvii] This coloniality of power, according to Anibal Quijano is built on the “coloniality of knowledge,”[cxlviii] and in a two-way relationship sustained by coloniality of power.

Coloniality and Social Polycentricism

Steytler would identify four important issues here; de-ethnicisation of indigenous institutions; “monoethnic hegemonies,” cultural relativism and ethnic competition for power which manifests as pan-tribalism, prebendalism and prebendal pan-tribalism.

First is the program of de-ethnicisation. As Steytler noted the “traditional authorities had lost their political powers.”[cxlix] “As the sole source of power, the colonial state also sought to destroy all competing locations of power and brought traditional authorities into its service.”[cl] Traditional authorities “were perceived as competing centres of loyalty, and the new rulers sought, in the patriarchal language of Hippolyt S. A. Pul, ‘to emasculate’ and ‘effeminate’ them in the name of de-ethnicising post-independence countries.”[cli] This according to Louis Munoz is traceable to the modernization paradigm[clii] of “transitional society,” where tradition is a “hindrance”[cliii] and whereby a “pejorative,” “primitive”[cliv] and yet “fixed and stable”[clv] “traditional society” is “substituted” by a modern “industrial society.”[clvi]

The second is the paradox of “monoethnic hegemonies” or tyranny of the major or minor ethnic group in spite of de-ethnicisation. Yet, there is a paradox to the “de-ethnicising post-independence countries” as “many one party states in the process turned into ‘monoethnic hegemonies’.[clvii] The prize is that the “control of political power enabled access to wealth and privilege for the privileged view or ethnic group.”[clviii]

The third is ethnic competition for power and it is the most fundamental. This is related to the paradox of “monoethnic hegemonies” which leads to ethnic competition for power by means of which according to Yash Ghai that “voting are still based on ethnicity;”[clix] [284] According to Munoz, in Nigerian context, this ethnic competition for power, called pan-tribalism (or simply tribalism), and is “traditionalism” or the ideological manipulation of tradition, as opposed to tradition or the “instinctive” or “natural” continuity.[clx] According to R. L. Sklar, the specie of “pan-tribalism” which is as a result of modern urbanization and the expression of the primordial sentiment of the new class is different from “communal partnership” found in townships where indigenous values and authorities thrive.[clxi] Tribalism, according to A. A. Akiwowo, is when geo-ethnic groups compete for “places in the class status and power systems of the new nations,”[clxii] through the ideological manipulation of “identity”[clxiii] or “primordial loyalties,” which may “have a religious, cultural or ethnic character.”[clxiv]

As well described by Munoz, pan-tribalists, with their deceptive and inchoate fusion of pre-colonial diverse peoples; historical revisions of post-colonial identities; and post-colonial irredentism and exclusion,[clxv] are seldom interested in the genuine continuity of traditions/civilizations evident within moral “primordial public” via “communal partnership.” Pan-tribalists are never interested in the genuine continuity of traditions/civilizations evident within moral primordial public, unlike the communal politics “which constitute a value per se,” for pan-tribalists, “it has primarily an instrumental value; it is a weapon to be used in the contest for political supremacy in the national arena.”[clxvi] Pan-tribalists are mostly Euro-American educated elites (like Kongi in Soyinka’s Kongi’s Harvest) who exploit primordial symbols like language and clothing, and who live in the cities to exploit ethnic/religious identities in their struggles for wealth and power. Sheldon Gellar also notes that

“Many societies in precolonial Africa were self-governing communities that fiercely defended their independence. The imposition of colonial rule was often accompanied by the demise of local liberties. During decolonization and after independence, African political elites placed more emphasis on gaining control of national level institutions rather than seeking to reestablish local liberties and decentralized democratic governance.”[clxvii]

In fact, R. Melson and H. Wolpe acknowledged that “it is probably more accurate to say conflict produces ‘tribalism’ than to argue, as conventional wisdom says, that tribalism is the cause of conflict.”[clxviii] The conflict is over the control of the over-centralized and amoral State. The conflict is over the creation of “monoethnic hegemonies,” according to Steytler, which would lead to the “control of political power” that “enabled access to wealth and privilege for the privileged view or ethnic group.”[clxix] It was in their pan-tribal and amoral struggles for wealth and power in Nigeria led to the collapse of the First Republic, military coups, the Civil War; prebendalism since the Second Republic; and the prebendal pan-tribalism in the present Fourth Republic. So, whenever the chicken came home to roost, there was no moral agency to confront it.

And the fourth element of social coloniality is the problem of cultural relativism. As Ghai argued, “that society is divided on the values of the constitution – divisions that are often articulated on the grounds of cultural relativism.”[clxx] And the cultural relativism is unfortunately strengthened or worsened by pan-tribalism. It is the real conflict.

The irony, as Munoz noted, is that “the introduction of universal suffrage” as one of the elements of modernization has “the adverse effect of politicizing and therefore consolidating existing parochialisms.”[clxxi] The tendency here is the concern for “rights” without responsibility, what Thomas Pangle calls outgrowth of the Lockean natural right – “‘‘natural right tradition of tolerance,’’ or ‘‘the notion that everyone has a natural right to the pursuit of happiness as he understands happiness’’.”[clxxii]

And often, this takes disparate directions based on cultural relativism. In this way, both “national integration” and “modernization” contribute to “politicization of ethnicity” or “tribalism.”[clxxiii] Integration, which sets the rules for competition between hundreds of “regional sub-national” groups in a democracy is built on constitutional exclusion[clxxiv] of indigenous authorities of the pre-modern political institutions[clxxv] and tyranny of the major or minor ethnic group in each administrative unit.[clxxvi] Worse, according to Munoz, economic in-equality is regulated to sustain this colonial system, robbing it of its legitimacy.[clxxvii] The question is why would modern natural right or human right assist the triumph of these parochialisms?

Apathy

The fatal consequence of all these parochialisms is the apathy for “the formal state (acting in its own interest or for an exclusive group)”[clxxviii] Steytler observed in Yash Ghai’s words the “‘overwhelming factor [of] the passivity of the people’[clxxix]– their “inability to act collectively”[clxxx] is an “important impediment to constitutionalism.”[clxxxi] This according to Tocqueville is the greatest impediment.

“It cannot be absolutely or generally affirmed that the greatest danger of the present age is license or tyranny, anarchy or despotism. Both are equally to be feared; and the one may as easily proceed as the other from the selfsame cause, namely, that “general apathy,” which is the consequence of what I have termed “individualism”: it is because this apathy exists, that the executive government, having mustered a few troops, is able to commit acts of oppression one day, and the next day a party, which has mustered some thirty men in its ranks, can also commit acts of oppression. Neither one nor the other can found anything to last; and the causes which enable them to succeed easily, prevent them from succeeding long: they rise because nothing opposes them, and they sink because nothing supports them. The proper object therefore of our most strenuous resistance, is far less either anarchy or despotism than the apathy which may almost indifferently beget either the one or the other.”[clxxxii]

According to Tocqueville, United States is the most perfect federal constitution in the world,[clxxxiii] but when ill adapted by a people without the republican manners of enlightened self-interest and of self-government becomes a disaster.[clxxxiv] He cited the examples of Mexico who adopted the American laws without the manners,[clxxxv] Mexico adopted the constitution of the United States, but turned into standing armies between them.[clxxxvi] These problems are the contemporary and great challenges in Africa apathy for public business and need to combat individualism.[clxxxvii] This is what happened with the fall of the Nigerian First Republic. Douglass C. North & Andrew R. Rutten suggested;

“Differences in norms of behavior can dramatically modify the consequences of formal rules. For example, the adoption of the United States Constitution by some Latin American countries has led to very different results than in the United States. Since norms appear to change more slowly than formal rules, their interaction with rules can result in radically contrasting paths of institutional evolution.”[clxxxviii]

Precisely, the two publics and the absence of a polycentric local government, entrenched by the coloniality of power, which produced pan-tribalists, led to the general apathy or absence of citizenship, which further led to the new gambits of prebendal despotism (Second Republic) and prebendal pan-tribalistic anarchy (Fourth Republic), in Nigeria. It is a vicious circle.

Polycentric Analysis

Aligica and Tarko give us an “intriguing insights” of how the existence of several centers for decision making without the “the overarching system of rules” [clxxxix] could break “down (into either authoritarianism or violent chaos)”[cxc] or that the “breakdown of polycentricity may give way either to a monocentric system (authoritarian or not), or to chaotic violent anarchy.” [cxci] This intriguing insight is coeval with Tocqueville’s explanation of anarchy and despotism.

Coloniality of Knowledge and Being

Fundamentally, these pathologies, de-ethnicisation of indigenous institutions; “monoethnic hegemonies,” cultural relativism and ethnic competition for power which manifests as pan-tribalism, prebendalism and prebendal pan-tribalism culminate in the coloniality of being, the lived experiences of colonized peoples. They are made possible by the coloniality of knowledge and enforced by the coloniality of power, as identified by Anibal Quijano.

The vital epistemological task of creating knowledge for the continuity of coloniality falls on the colonial and amoral public who in turn are servant of the destructive elements of the Eurocentric knowledge system, for example the Huntington’s kind of modernization. And this task is directed at denial and repression of the knowledge system of the conquered, who are now being relegated, exploited and excluded as an inferior. For example, Folala argued that our schools modelled after Euro- American political models have

“therefore, brought about the ruination of the reputation of indigenous values and cultures, deactivating them from being very present in the business of emancipation and development … Unwittingly, the unapologetic repudiation of African values perpetuated during the colonial era is now being reproduced by African themselves in utter disregard for the dangers inherent in that.” [cxcii]

Coloniality of knowledge transmogrify colonial subjects to “victims of the coloniality of being” banished in “a condition of inferiorisation, peripheralization, and dehumanization.”[cxciii] By this modern and artificial cultural systems, with de-humanizing pathologies are created to sustain and empower what is equally artificially regarded as the humane Euro-American economic and knowledge production systems. Understanding these is coeval to understanding our Euro-American modernity.[cxciv] It is this policy of de-ethnicisation that Wole Soyinka called “the policy of glamourised fossilism” in his 1965 Kongi’s Harvest, which dramatically led to both despotism and anarchy. In this play, even the arrested development of drums signifies apathy.

Coloniality and Economic Polycentricity

There three related and fundamental ways coloniality affects the possibility of economic polycentricity. The first is that anarchy and despotism frustrate economic progress. The second is the destruction of the surest basis that enlightened self-interest can be built against apathy. The third is the continuity of a colonial economy made possible by the constitutional exclusion of the primordial public and the program of de-ethnicisation.

Firstly, the paradox of the post-colonial orders, according to Steytler, is simple enough; “The centralisation of the African state did not, as promised, lead to development, but to its opposite – conflict and skewed underdevelopment.” [cxcv]“The need of “a strong centre to make sub-national government work” leads to “state failure and the absence of the rule of law,”[cxcvi] and the insecurity of the failing state.[cxcvii] Unfortunately, the existence of two republics with respect to the constitutional and formal exclusion of the “traditional and informal governance structures” have contributed to both anarchy and despotism. As a result, the Steytler noted

“Postcolonial Leviathans followed in succession, neither effecting peace nor securing legitimacy, but attracting ‘the violence of enemies’ and rebellion. These followed two broad trajectories: exit or contest. Secession movements sprang up in, among other countries, Nigeria, Sudan, Congo and Ethiopia. Most often it was the contest for the control of the state. Most authoritarian states survived only through support from the superpowers, and the end of the Cold War left many of them fragile or besieged by civil war.”[cxcviii]

The conflicts and absence of political stability have obviously frustrated economic development.

Secondly, the interesting thing is that Tocqueville built his moral system on economic sense. “Faithful to the requirements of equality, Tocqueville appeals to the self-regarding instincts of man and strives to erect upon this basis a species of public morality and of patriotism: he would make men virtuous by teaching them that what is right is also useful.” [cxcix] The foundation of the public or social order rests upon enlightened selfishness: each individual accepts the view that “man serves himself in serving his fellow creatures and that his private interest is to do good.” [cc] and that men “must come to see the desirability of postponing the immediate gratification of their desires in the expectation of a more certain or greater degree of satisfaction at a later time, an expectation arising from the contribution of the common welfare to their own well-being.”[cci] Self-interest rightly understood is “understood primarily in an economic sense—it is a concern with the most immediate, tangible, material signs of a man’s well-being.” [ccii] According to Marvin Zetterbaum;

“To rely upon self-interest rightly understood necessitates, of course, that self-interest be rightly understood. Within the context of the Democracy, self-interest is understood primarily in an economic sense—it is a concern with the most immediate, tangible, material signs of a man’s well-being. Out of an enlightened regard for one’s own material welfare, a good other than an economic one will emerge: patriotism or public spiritedness is the by-product arising from the intelligent pursuit of one’s own interest.” [cciii]

Without a vibrant economic platform for this “economic sense,” self-interest rightly understood is not possible. The presence of apathy is the same as the absence of “initiative and optimism,” necessary for self-interest rightly understood as well as for economic progress. Tocqueville noted that “The local tradition has done so, … by keeping alive a certain cooperative initiative and a belief in the possibilities for self-help through association, which is likely to be much easier at the local level.” [cciv] Secondly, Tocqueville also noted that the spread of equality makes all country follow manufactures and commerce and become alike – so they dread war – interests of all are interlaced.[ccv] Along the same line, Carol M. Rose stated that “a nation’s commercial success depended on the initiative that could only be generated in free institutions.”[ccvi]

As a result, without citizens and self-interest rightly understood, our local authorities go cap-in-hand for federal allocations, rather than becoming productive economic centers.

The third is the continuity of a colonial economy made possible by the constitutional exclusion of the primordial public and the program of de-ethnicisation. During the making of the 1979 Constitution by the military regime, which was modified to the 1999 Constitution by another military regime, the subject matter of mixed economy created some controversy. There was an objection to the ambiguous use of the term mixed economy. Ola Oni, for example, made two connected points in December of 1976. The first was that mixed economy is a placeholder for being “a satellite economy” and “neo-colonial capitalist economy.” According to him,

“the ideology of mixed economy seeks to modernize the liberal capitalism of Adam Smith and fit it into Nigerian conditions … mixed economy is used in reference to a satellite economy … it means really a neo-colonial capitalist economy … which the public sector promotes capitalism under the domination of world imperialism.” And “the main supporters of this ideology can be found among those who already hold leading positions in our society. These are the foreign capitalists, their domestic capitalist aspirants, the bourgeois bureaucrats, academicians and all those who benefit from the present neo-colonial capitalist arrangement.”[ccvii]

Secondly, Oni connected the “neo-colonial capitalist economy” to the pan-tribal and prebendal elite. Oni stated that the “petty-bourgeois” hopes to keep Nigeria together by “maintaining a balance of ethnic interest, creating more and more states to appease the competitive acquisitive struggle of these bourgeois ethnic leaders.” [ccviii] In short, the pan-tribal and prebendal elite combine to further a neo-colonial economy.

Whilst disregarding the bourgeois sneer, it can be acknowledged that there is nothing particularly wrong about mixed economy which is an economic system combining private and state enterprise. The idea of non-partisan mixed economy itself could be said to be Tocquevillian because Tocqueville was neither Left nor Right.[ccix] Tocqueville, according to Gellar “attacked the 18th century philosophes and revolutionaries for creating “an imaginary ideal society in which all was simple, uniform, coherent, equitable and rational.”[ccx] Deng Xiaoping, the quintessential Chinese reformer, also stated, “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.” It was Xiaoping who engineered the renaissance of the Chinese traditional polycentricity as the “Chinese characteristic.”

What is wrong in our own case is that there is no black nor white cat, but the colonial cat who is propped to power through intra and inter ethnic competition for power, and rewarded to exclude the primordial public from power. Having mentioned Xiaoping above, it would be useful to say a few things about polycentricity also in China as a contrast to what we have in Nigeria. David S.G. Goodman and Gerald Segal, in a 1994 article’ China After Deng: The Prospects for Polycentrism and Democratization, wrote that “China is already characterized by a high degree of regionalism that has dramatically altered the workings of its political system and is coming to influence domestic style. National unity may not be in question but China increasingly polycentrist.”[ccxi] They noticed how within China “the impact of de-centralization, regionalism, national economic integration all seem to indicate the greater diffusion of political power,”[ccxii] As a result, even China, and not only United States is more polycentric than us. More than anything both Goodman and Segal noted a Chinese modernization that has not abandoned its past.

“If anything through international economic integration—specific to each economic region – China’s provinces are becoming more rather than less autonomous, least in relation to central government. On the surface an effective federalism seems a distinct possibility in practice, though not in name or law not least because of the absence of a tradition of a rule of law. Chinese culture has long been polycentric; it was only the rigid conformity of the late Qing Empire and the state under Mao sought to portray its centralist aspects.” [ccxiii]

This again, goes to show the non-ideological utility of polycentricism. On the colonial cat who is propped to power through intra and inter ethnic competition for power, and rewarded to exclude the primordial public from power, no other time in history is more revealing than now with President Bola Tinubu’s neo-liberal policies, being pushed by IMF and World Bank with his floating of Naira and removal of subsidies, with the devastating effects on the people.

Polycentric Analysis

The absence of the third element of polycentricity, the existence of spontaneous order, is the same as the absence of “initiative and optimism” and the capacity for self-interest rightly understood. The “existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life,”[ccxiv] which is also related to three things; “the freedom of entry and exit in a particular system;” incentives to “enforce general rules of conduct;” and capacity for “reformulation and revision of the basic rules” with procedural “rules on changing rules” and cognitive rules with “an understanding of the relationship between particular rules and the consequences of those rules under given conditions.” [ccxv] The absence means of spontaneous order is the same as absence of the choice of “entry and exit”, and basically the capacity for improvements, for optimism.

Also, As earlier stated, any “island of polycentric order entails and presses for polycentricism in other areas, creating a tension toward change in its direction,” [ccxvi] the same goes for monocentric islands leading to “an unstable coexistence” [ccxvii] between monocentrism and polycentricity. Thus, political polycentricity within the local authorities would have pressed for polycentricism in economic areas. It is for this reason that the primordial public with the diverse polycentric proclivities are rigidly contained and kept out of Nigerian constitutional formation, due to their propensity for spontaneity. That is what Soyinka meant by “fossilism.”

Coloniality of Knowledge, of Power, and of Being

We would not come to the full understanding of the pathologies of over-centralization until we have realized that the main reason for the absolute rule of the moral “primordial public” by the amoral “civic public” is simple enough. It is basically to secure over-centralization of power, an organized chaos, and hence absolute access to combined economic control; production and exportation of raw materials and maintenance of market for imported finished products. Fundamentally, this is the coloniality of knowledge, as identified by Anibal Quijano, which “appropriates meaning” just as the coloniality of power stated above “takes authority, appropriates land, and exploits labor.”[ccxviii] As Gellar noted “Colonial laws also expropriated large tracts of indigenous land which was transferred to the colonial state or the settler population. Property rights and access to natural resources constitutes one of the major arenas of politics.” [ccxix] This continues in our post-independent era.

Here is one of the most powerful manifestation of coloniality based on international division of labour between the Euro-Americans and Africans, well captured by Ramón Grosfoguel, [ccxx] based on what Anibal Quijano identified as a racial hierarchy and racial division of labour by means of a system of serfdom.[ccxxi] This is the root of the on-going neo-liberal capitalism built to sustain a colonial system via racist and patriarchal logic.[ccxxii] Kolawole Ogundowole also wrote that the “major” African contradiction is not the contradiction between capitalism and socialism-communism, but what he called “dialectical realism” which reveals that the major contradiction is between “forces of imperialism, neo-colonialism and subjugation:” and the “forces of self-reliancism and national recovery.”[ccxxiii]

We are reminded of the changed mind of Angus Deaton, the Economics Nobel Prize winner, on neo-liberal economics which he recently shared on IMF website. Deaton critiqued the short-term approach of neo-liberal economics compared to historians who “often do a better job than economists” [ccxxiv] He deployed the situation where “unions” who “once raised wages for members and nonmembers” but now “have little say compared with corporate lobbyists.” [ccxxv] Unions “brought political power to working people in the workplace and in local, state, and federal governments. Their decline is contributing to the falling wage share, to the widening gap between executives and workers, to community destruction, and to rising populism.” [ccxxvi] Deaton stated two important things that are relevant here. Firstly, Deaton noted;

“Our emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game. Without an analysis of power, it is hard to understand inequality or much else in modern capitalism.”[ccxxvii]

Secondly, he argued for a two-way relationship between the economists on one hand, and the “philosophers, historians, and sociologists” on the other hand. [ccxxviii] On the side of the economists, he posited;

“In contrast to economists from Smith and Marx through John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, and even Milton Friedman, we have largely stopped thinking about ethics and about what constitutes human well-being. We are technocrats who focus on efficiency. We get little training about the ends of economics, on the meaning of well-being—welfare economics has long since vanished from the curriculum—or on what philosophers say about equality. When pressed, we usually fall back on an income-based utilitarianism. We often equate well-being to money or consumption, missing much of what matters to people. In current economic thinking, individuals matter much more than relationships between people in families or in communities.” [ccxxix]

The “importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game” in relations to economics do not only emphasize the importance of the interconnectedness of polycentricity, it reveals what “power” is simply.

We are back again to Falola expose that “response, reaction, and resistance to hegemonic epistemic traditions of the European world, which began and ended before the conferment of independence on the colonized peoples, cannot necessarily explain the situation of colonization, which has continued to manifest itself even after the physical termination of the colonial imperialists from the power bases of different African countries.”[ccxxx] The realities of the causal “two publics” is one powerful handle of coloniality which must be dismantled before we could attempt a sustainable political stability towards the much needed economic progress. Against this coloniality we must de-colonize. Decoloniality is a form of “epistemic disobedience”[ccxxxi] [Walter D. Mignolo]; “epistemic de-linking”[ccxxxii] [Walter D. Mignolo]; “decolonisation of … epistemologies”[ccxxxiii] [Toyin Falola]; and “epistemic reconstruction”[ccxxxiv] [Aníbal Quijano] from contemporary legacies of coloniality.

What the military ought to have done in 1979?

“Providence,” Tocqueville tells us, “has not created mankind entirely independent or entirely free. It is true that around every man a fatal circle is traced beyond which he cannot pass; but within the wide verge of that circle he is powerful and free.”[ccxxxv] Tocqueville’s work appears as an admonition to men to make the best of the lot awarded them by God—men cannot determine whether conditions will or will not be equal, but theirs is the responsibility whether equality will lead to wretchedness or to greatness, to slavery or to freedom … To accomplish this end, Tocqueville calls for a “new science of politics,” one adequate to the novel conditions occasioned by the triumph of equality.”[ccxxxvi]

Towards this end, Tocqueville observed in the United States and identified the self-interest rightly understood which is understood primarily in an economic sense as the most fundamental basis of manners to confront general apathy and individualism, both of which have made anarch and despotism posssible. Furthermore, Tocqueville held that the “natural passion for freedom must be supplemented by the political art, an art which Tocqueville finds has been practiced in an exemplary way by America.” [ccxxxvii] Marvin Zetterbaum also noted;

“The American experience suggests for the resolution of the democratic problem certain democratic expedients, such as local self- government, the separation of church and state, a free press, indirect elections, an independent judiciary, and the encouragement of associations of all descriptions. It must be recognized that Tocqueville does not simply recommend the adoption of each and every American practice. Although he admires the federal system, for example, he argues that such a complicated mechanism is wholly unsuited to the temperament and realities of European political life. More than anything else, America provides the principles, such as the principle of self-interest rightly understood, upon which a respectable democratic order might be constructed.” [ccxxxviii]

And the most important expedient is the local government. Free associations are the schools of self-interest rightly understood. For Tocqueville, the science of association, is the mother of science in a democracy,[ccxxxix] most important of which is local self- government. As Steytler noted, the local government is the “participatory institutions of self-government,”[ccxl] simply. Tocqueville thought that only by association can people stand against the government[ccxli] and that voluntary associations are to “supply the individual exertions of the nobles, and the community would be alike protected from anarchy and from oppression.”[ccxlii] The “principle of self-interest rightly understood – “the heart of Tocqueville’s resolution of the problem of democracy,” [ccxliii] is but a product of the local self-government; “the locus of the transformation of self-interest into patriotism” … “transform essentially selfish individuals into citizens whose first consideration is the public good.” [ccxliv]

“The Americans have combated by free institutions the tendency of equality to keep men asunder, and they have subdued it. The legislators of America did not suppose that a general representation of the whole nation would suffice to ward off a disorder at once so natural to the frame of democratic society, and so fatal: they also thought that it would be well to infuse political life into each portion of the territory, in order to multiply to an infinite extent opportunities of acting in concert for all the members of the community, and to make them constantly feel their mutual dependence on each other. The plan was a wise one.”[ccxlv]

“Tocqueville’s native France provided an excellent example of the difficulty of maintaining the viability of young democracies which lacked traditions of political freedom. Most of the new African states that emerged after obtaining their independence experienced similar kinds of problems in sustaining democracy.” [ccxlvi] According to Sheldon Gellar

“In America, Tocqueville discovered that the absence of administrative centralization and the existence of multiple and diffuse sources of political authority permitted citizens to participate directly in the management of public affairs to solve their problems. The practice of citizen participation in local self-government described and advocated by Tocqueville as a concrete manifestation of popular sovereignty had little in common with notions of participation stressing citizen involvement in selecting national rulers and articulating opinions and interests that might or might not be taken into consideration by central government. The kind of democracy envisioned by Tocqueville promoted self-government and the active participation of citizens in the management of local affairs. People learned how to work together and how to be self-governing within the framework of family, neighborhood, village, and other community-based institutions. For Tocqueville, these institutions needed to enjoy a certain degree of autonomy from the state in order to flourish. Free self-governing institutions and associations level provided a bulwark against state tyranny.” [ccxlvii]

If the science of association, is the mother of science in a democracy (632, 382), and local self- government is the most important of the science of association, then decoloniality, that is, the “epistemic” disobedience or de-linking; the decolonisation of epistemologies or epistemic reconstruction demands us to “infuse political life into each portion of the territory, in order to multiply to an infinite extent opportunities of acting in concert for all the members of the community, and to make them constantly feel their mutual dependence on each other.” Therefore, self-government and the active participation of citizens in the management of local affairs demands two things.

First is the complete decentralization and constitutionalising the local self-government with all the three elements of polycentricism; (1) The existence of many centers for decision making, (2) the existence of a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced), and (3) the existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life.”[ccxlviii]

Secondly, is the decolonization and the destruction of the two publics of “the formal state (acting in its own interest or for an exclusive group)” and the “informal governance institutions (social institutions and processes working for people’s daily survival)”[ccxlix] into one single moral and polycentric public “the diversity of social forces of a polycentric political, economic and social system, in whose interests the constitution is enforced.”[ccl]

These moral primordial publics were colonized one by one to create Nigeria. In the same way they are to be granted real independence within a constitutional and a polycentric order, as long as the overarching rules exist. The implication is accommodating two major and independent centers for decision making within each local self-government; now a moral center democratic center and equally the moral primordial center, all based on “the existence of a single system of rules (be they institutionally or culturally enforced)” and “the existence of a spontaneous social order as the outcome of an evolutionary competition between different ideas, methods, and ways of life.”[ccli] Several existing town/city unions, could be easily accommodated in the former, whilst the “primordial public” could be accommodated in the latter.